Corticosteroid Hyperglycemia Risk Calculator

Your Risk Assessment

This tool calculates your risk of developing corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia based on key factors from clinical guidelines.

When you’re prescribed corticosteroids for inflammation, autoimmune disease, or severe asthma, the goal is relief. But for nearly half of hospitalized patients, that relief comes with an unexpected side effect: dangerously high blood sugar. This isn’t just a minor blip on a glucose monitor-it’s corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia, a real and often overlooked metabolic crisis that can turn into full-blown diabetes if left unchecked.

Why Steroids Spike Your Blood Sugar

Corticosteroids like prednisone, dexamethasone, and hydrocortisone don’t just calm your immune system-they mess with your body’s entire glucose system. They don’t just make you resistant to insulin; they actively shut down your pancreas’s ability to make it. In the liver, these drugs crank up glucose production by nearly 38%, flooding your bloodstream with sugar. At the same time, your muscles stop absorbing glucose the way they should-uptake drops by over 40%. Fat cells start breaking down faster, spilling free fatty acids into your blood, which further blocks insulin from working. And in your pancreas, beta cells that normally release insulin get suppressed, with key glucose-sensing proteins like GLUT2 and glucokinase falling by more than 20% after just one high dose.This isn’t type 2 diabetes. It’s different. In type 2, insulin resistance builds slowly over years. Here, it hits fast-sometimes within hours of taking your first pill. And the pattern is unique: your blood sugar spikes hard in the morning, right after your steroid dose, then drops back toward normal by evening. That’s why checking your glucose only once a day, or only in the morning, can miss the full picture. You might think you’re fine, but your nighttime sugars could be climbing unnoticed.

Who’s at Risk-and How Bad It Can Get

Not everyone on steroids develops high blood sugar, but certain people are far more vulnerable. If your BMI is over 30, you’re over three times more likely to develop hyperglycemia than someone with a normal weight. If you already have prediabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, your risk jumps nearly fivefold. Even people who’ve never had a glucose issue can slip into steroid-induced diabetes when given high doses-19% to 32% of patients without prior diabetes develop it when on doses above 20 mg of prednisone daily.The dangers aren’t theoretical. In severe cases, 4.7% of patients develop hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state-a life-threatening condition where blood sugar soars past 600 mg/dL, dehydration sets in, and organs start failing. Diabetic ketoacidosis, though less common, still occurs in 2.3% of hospitalized patients on steroids. And even if you survive the acute phase, prolonged high glucose levels damage blood vessels, increasing your long-term risk of kidney disease, nerve damage, and heart problems.

How to Monitor Correctly

The old way of checking blood sugar once a day is dangerously outdated. Modern guidelines say you need to start monitoring within 24 hours of starting steroids. For high-risk patients-those on high doses, overweight, or with prior glucose issues-you need at least two checks a day: fasting in the morning and two hours after your largest meal.But here’s the catch: if you’re on a once-daily morning steroid, your insulin needs aren’t symmetrical. You need more insulin in the morning, less in the afternoon. Sliding scale insulin-where you give a set amount based on a single glucose reading-isn’t enough. Studies show basal-bolus insulin regimens (a long-acting insulin plus fast-acting insulin with meals) are 35% more effective at keeping glucose in range than sliding scale alone.

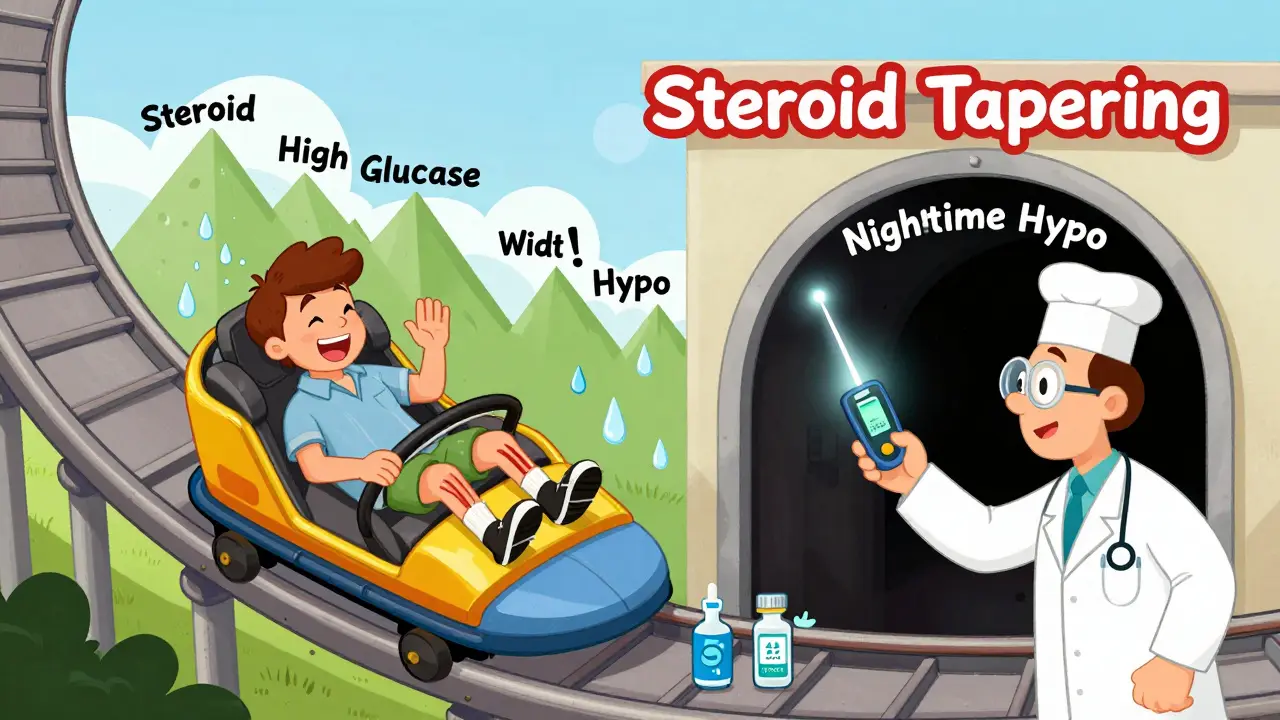

Even more surprising: continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) catch 68% more high blood sugar episodes than fingersticks. Why? Because they see the spikes you miss-like overnight surges or dips during steroid tapering. About 23% of patients on tapering doses experience unexpected hypoglycemia, often at night, because their insulin dose hasn’t been adjusted down fast enough. CGMs give real-time alerts, so you don’t wake up confused, sweaty, and shaky.

When to Start Insulin

Many doctors hesitate to start insulin, fearing it means the patient now has “diabetes.” But steroid-induced hyperglycemia isn’t permanent for most. It’s a temporary metabolic crisis. The goal isn’t lifelong insulin-it’s safe control while the steroids are doing their job.Here’s what works: if two consecutive glucose readings are above 180 mg/dL, start insulin. Don’t wait for 200, 250, or 300. The Mayo Clinic’s protocol, adopted across several hospitals, reduced complications by over 50% by acting early. For patients with pre-existing diabetes, expect to increase your insulin dose by 20% to 50%. For those without prior diabetes, basal-bolus insulin is the gold standard. Oral diabetes drugs like metformin or SGLT2 inhibitors? They often don’t cut it. Steroid-induced hyperglycemia is too severe, too rapid, and too insulin-deficient for pills alone.

What Happens When Steroids Stop

Tapering steroids is where things get tricky. As the steroid dose drops, your insulin resistance fades-but your pancreas doesn’t snap back immediately. That creates a dangerous window: your insulin dose is still high, but your body’s need for it is dropping fast. This is the most common time for hypoglycemia to strike.Patients report a “rollercoaster effect”-highs during treatment, then sudden lows during tapering. One survey found 67% of patients experienced unexpected low blood sugar when their steroid dose was being reduced. That’s why you can’t just stop insulin when steroids stop. You need to reduce insulin gradually, guided by frequent glucose checks. Many patients need insulin for weeks after their last steroid dose.

Why So Many Hospitals Get It Wrong

Despite clear guidelines, only 58% of non-critical care units in U.S. hospitals have formal protocols for managing steroid-induced hyperglycemia. That means nearly half of patients are being monitored haphazardly. Nurses might not know to check glucose after the first steroid dose. Doctors might not realize the morning-only pattern. Pharmacists might not flag the risk when dispensing prednisone.One study found patients in hospitals without protocols waited 43% longer to get treatment. That delay can mean the difference between a manageable glucose spike and a trip to the ICU. Even more troubling: only 44% of non-endocrinology physicians correctly identify the classic morning hyperglycemia pattern of steroid-induced diabetes. If the doctor doesn’t understand the pattern, they won’t order the right tests or adjust insulin properly.

The Bigger Picture: Cost, Care, and the Future

This isn’t just a clinical issue-it’s an economic one. Each year, over 2 million U.S. hospital admissions involve corticosteroids. Managing glucose properly adds cost for monitoring and insulin, but it saves money overall: on average, patients who get proper care leave the hospital 1.8 days sooner. That’s over $2,300 saved per admission.Looking ahead, research is moving fast. The NIH is testing a machine learning tool that predicts who’s at risk by combining BMI, HbA1c, steroid dose, and even genetic markers like GR-1B polymorphisms. Early results show 84% accuracy. Meanwhile, drug companies are developing “steroid-sparing” drugs and tissue-selective glucocorticoid receptor modulators that fight inflammation without wrecking glucose control. Three are already in Phase II trials, cutting hyperglycemia rates by over 60% compared to standard steroids.

The message is clear: corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia is common, dangerous, and treatable. But only if you know what to look for-and act fast. It’s not about blaming the steroid. It’s about understanding its metabolic toll and responding with precision, not guesswork.

Can corticosteroids cause permanent diabetes?

In most cases, no. Steroid-induced hyperglycemia usually reverses once the steroid dose is lowered or stopped. But if you already had prediabetes or insulin resistance before starting steroids, the stress on your pancreas might reveal an underlying condition that was already developing. In those cases, you may need ongoing diabetes management-even after stopping steroids. It’s not the steroids that caused diabetes permanently; they just accelerated what was already there.

Is metformin enough to treat steroid-induced high blood sugar?

Usually not. Metformin helps with insulin resistance, but steroid-induced hyperglycemia involves both resistance AND a sharp drop in insulin production. Studies show oral medications like metformin, sulfonylureas, or SGLT2 inhibitors fail to control glucose in over 70% of patients on high-dose steroids. Insulin is the most reliable and effective treatment during active steroid therapy because it directly replaces what the pancreas can’t make.

How often should I check my blood sugar if I’m on prednisone?

If you’re on 20 mg or more of prednisone daily, check your blood sugar at least twice a day: once fasting in the morning and again 2 hours after your largest meal. If you’re high-risk-overweight, older, or with prior glucose issues-check four times a day, including before dinner and at bedtime. If you’re on a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), you’ll get real-time trends and alerts, which is ideal during steroid tapering when lows can sneak up.

Why does my blood sugar spike only in the morning?

Because most steroid doses are taken in the morning to mimic the body’s natural cortisol rhythm. The drug peaks in your bloodstream 4-6 hours after ingestion, which is when insulin resistance hits hardest. Your liver dumps sugar, your muscles stop taking it in, and your pancreas can’t keep up. By afternoon and evening, the steroid’s effect weakens, so glucose levels often drop back toward normal. That’s why checking only at night can miss the problem entirely.

Should I stop taking steroids if my blood sugar goes high?

Never stop steroids on your own. They’re prescribed for serious conditions like severe asthma attacks, autoimmune flare-ups, or organ transplant rejection. Stopping suddenly can cause adrenal crisis, a life-threatening emergency. Instead, tell your doctor immediately. They can adjust your insulin or steroid dose safely. The goal is to control your blood sugar while continuing the steroid treatment you need.

Can I use a CGM if I’m not diabetic?

Yes, and you should. Continuous glucose monitors aren’t just for people with diagnosed diabetes. Many hospitals now use them for patients on high-dose steroids-even those with no prior glucose issues. CGMs catch dangerous highs and lows that fingersticks miss, especially overnight. They’re especially useful during steroid tapering, when blood sugar can swing unpredictably. Talk to your doctor about a short-term CGM prescription if you’re on steroids for more than a week.

The History and Development of Chlorthalidone

The History and Development of Chlorthalidone

Chloroquine: Uses, Side Effects, Dosage & the Latest COVID‑19 Findings

Chloroquine: Uses, Side Effects, Dosage & the Latest COVID‑19 Findings

Why the First Generic Filer Gets 180 Days of Market Exclusivity

Why the First Generic Filer Gets 180 Days of Market Exclusivity

Esophageal Cancer Risk from Chronic GERD: Key Red Flags You Can't Ignore

Esophageal Cancer Risk from Chronic GERD: Key Red Flags You Can't Ignore

JAK Inhibitors: What You Need to Know About Infection and Blood Clot Risks

JAK Inhibitors: What You Need to Know About Infection and Blood Clot Risks

Melissa Taylor

December 15, 2025 AT 22:08Just had a patient on high-dose prednisone for lupus flare-glucose hit 320 mg/dL by noon. We started basal-bolus insulin same day. No ICU, no DKA, just steady control. This post nails it: early insulin saves lives, not just numbers.

John Brown

December 16, 2025 AT 16:02Been a nurse for 12 years and I still see hospitals skip the morning glucose check. It’s wild. Steroid spikes are predictable-why are we still guessing? CGMs aren’t luxury gear anymore. They’re standard care for anyone on >20mg prednisone.

Benjamin Glover

December 17, 2025 AT 10:45Typical American medical overreach. Insulin for every glucose spike? We used to manage this with diet and observation. Now it’s all algorithms and monitors. Pathetic.

Raj Kumar

December 19, 2025 AT 04:27Bro, this is real. I’m a med student in Delhi and we had a guy on dexamethasone for GBS-his sugars went nuts. We didn’t have CGMs, so we did 4x checks. He was fine by discharge. But yeah, insulin > metformin here. No debate.

Jocelyn Lachapelle

December 19, 2025 AT 06:41My aunt was on steroids after a transplant and they didn’t check her sugars till day 4. She ended up in DKA. Don’t wait. Check early. Check often. This isn’t optional.

RONALD Randolph

December 20, 2025 AT 10:23THIS. IS. NON-NEGOTIABLE. The data is irrefutable. Sliding scale is obsolete. Basal-bolus is gold standard. CGMs are essential. And yet-58% of hospitals lack protocols? This is malpractice by inertia. Someone needs to be held accountable.

Christina Bischof

December 21, 2025 AT 15:20My dad’s on prednisone for PMR. We got him a CGM after one scary night low. Honestly? It’s been a game-changer. He sleeps better now. And we catch highs before they become emergencies. Worth every penny.

Michelle M

December 22, 2025 AT 07:50It’s funny how we treat steroids like magic bullets and ignore their cost to the body. We fix the inflammation but break the metabolism. Maybe the real question isn’t how to manage the sugar-but whether we need to be giving so much of this stuff in the first place.

Lisa Davies

December 24, 2025 AT 02:10CGM for steroid patients = absolute must 😊 I got one for my sister on 40mg prednisone-she cried when she saw how high her nights were. We adjusted insulin, she’s fine now. Tech isn’t scary-it’s lifesaving 💪

Nupur Vimal

December 25, 2025 AT 13:07You all act like this is new info but we’ve known this for decades. In India we’ve been using insulin for steroid hyperglycemia since the 90s. Why is the US so slow? Maybe because nobody wants to admit their system is broken

Cassie Henriques

December 27, 2025 AT 04:24Interesting that GLUT2 and glucokinase downregulation is cited-this is the exact mechanism behind the morning spike. Most clinicians don’t know the molecular why, just the clinical what. That’s why protocols lag. We need more endo-ed in med school.

Jake Sinatra

December 27, 2025 AT 04:49As a hospitalist, I can confirm: early insulin initiation reduces ICU transfers by over 50%. The Mayo protocol is not just good practice-it’s the bare minimum. Any facility not implementing this should be audited.

Mike Nordby

December 28, 2025 AT 00:41One of the most important posts I’ve read this year. This isn’t just about glucose-it’s about systemic failure in care delivery. We have the tools. We have the evidence. We just need the will to act.

John Samuel

December 28, 2025 AT 16:57Imagine if every patient on steroids got a free CGM for the duration of therapy. No more guessing. No more midnight panic attacks. No more preventable DKA. This isn’t a cost-it’s an investment in dignity, safety, and human life. Let’s make it standard.

Sai Nguyen

December 30, 2025 AT 10:07Why are we letting Americans dictate global standards? In my country, we don’t overmedicate with insulin. We use diet and patience. This post reads like a pharmaceutical sales pitch.