Liver Medication Safety Calculator

This calculator helps determine appropriate dose adjustments for medications based on liver function. Your liver's ability to process drugs is critical for safety. The calculator uses your liver function score (Child-Pugh or MELD) and the type of medication to recommend safe dosing.

Step 1: Select Liver Function Assessment

Step 2: Select Medication Type

Step 3: Enter Liver Function Score

Step 4: Select Specific Medication

When your liver is damaged, your body doesn't just struggle to filter toxins-it also stops handling medications the way it used to. Many people assume that if a drug works for someone with a healthy liver, it’ll work the same way for someone with liver disease. That’s not true. In fact, reduced clearance due to liver disease is one of the most underrecognized risks in modern prescribing. It’s not about taking too many pills. It’s about how your body processes them-and when your liver is failing, that process breaks down in ways that can be deadly.

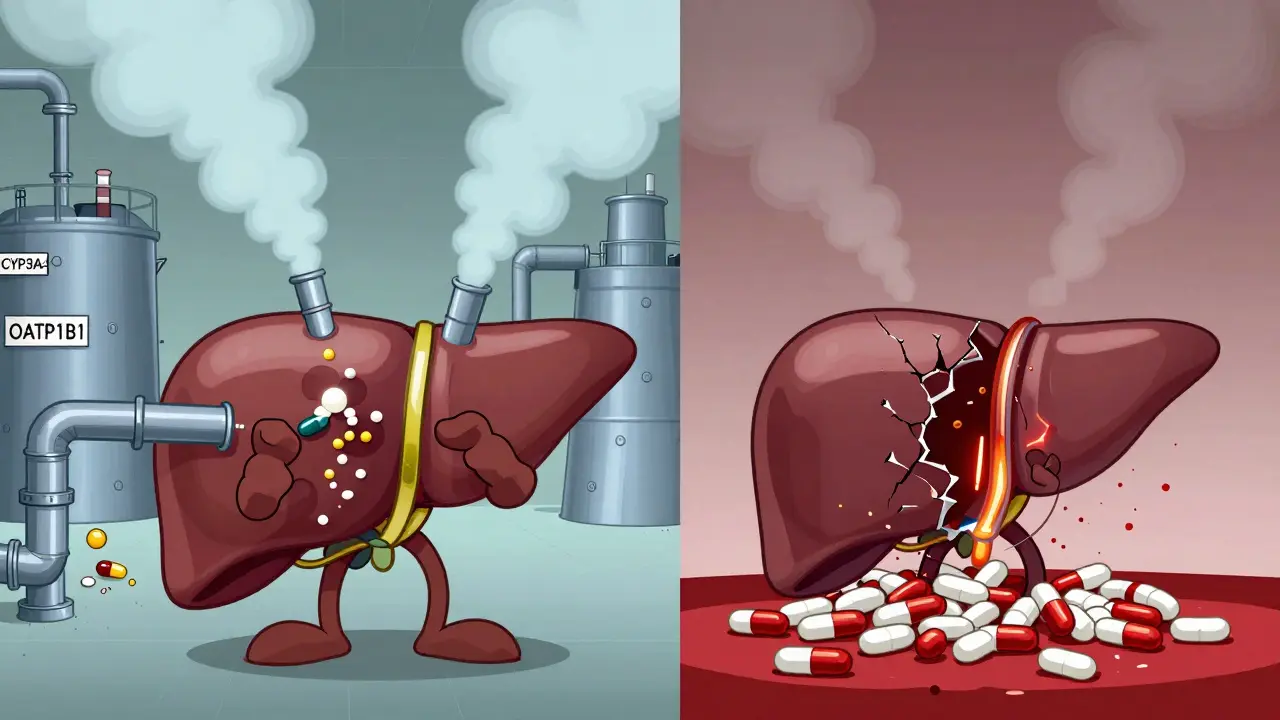

How the Liver Normally Processes Drugs

The liver isn’t just a filter. It’s a chemical factory. About 70% of all prescription drugs rely on it for clearance. This happens through two main paths: metabolism (breaking the drug down) and biliary excretion (pushing it into bile to leave the body). Key enzymes like CYP3A4 and CYP2E1 do the heavy lifting, turning drugs into forms the kidneys can flush out. Transporters like OATP1B1 help move drugs into liver cells so they can be processed. When all this works, you get predictable drug levels-enough to help, not enough to harm.What Changes When the Liver Fails

In cirrhosis or advanced liver disease, things fall apart. Blood flow to the liver drops from 1.5 liters per minute to as low as 0.8 liters. Liver cells shrink and die-up to 50% loss in hepatocyte numbers. Portosystemic shunts form, letting blood bypass the liver entirely. Up to 40% of blood flow skips detoxification. This means drugs that should be broken down on their first pass through the liver now flood into your bloodstream unchanged. Enzyme activity plummets. CYP3A4, which handles half of all common drugs, drops by 30-50%. CYP2E1 falls by 40-60%. Transporters like OATP1B1 lose up to 70% of their function. The result? Drugs stick around longer. Their half-lives stretch. What used to be a once-daily dose can build up to toxic levels in just a few days.High vs. Low Extraction Drugs: Why It Matters

Not all drugs are affected the same way. The key is whether they’re high- or low-extraction drugs.- High-extraction drugs (like fentanyl, morphine, propranolol) depend on liver blood flow. If blood flow drops, clearance drops. These drugs are cleared fast in healthy people-but in cirrhosis, they can accumulate dangerously.

- Low-extraction drugs (like diazepam, lorazepam, methadone) depend on enzyme activity. Even small drops in CYP enzymes mean big changes. These make up 70% of all commonly prescribed drugs. That’s why most patients with liver disease are at risk.

Real-World Consequences: Drugs That Can Turn Deadly

Here’s what happens when dosing isn’t adjusted:- Opioids (fentanyl, oxycodone): Even standard doses can cause severe sedation or coma. Liver disease makes the brain 30-50% more sensitive to them. Hepatic encephalopathy can be triggered by a single opioid pill.

- Benzodiazepines (diazepam, alprazolam): These form active metabolites that linger. In cirrhosis, diazepam’s half-life can jump from 20 hours to over 100 hours. Lorazepam, which doesn’t form active metabolites, is safer-but still needs a 25-40% dose cut.

- Warfarin: Clearance drops by 30-50%. A standard 5 mg dose can push INR levels into the danger zone. Dose reductions of 25-40% are often needed.

- Ceftriaxone: A common antibiotic. In cirrhosis, peak concentrations can spike 40-60% higher than normal. That raises the risk of kidney injury and seizures.

And it’s not just these. A 2023 study in NEJM found that 22.7% of patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis failed antiviral treatment for hepatitis C-not because the drug didn’t work, but because they were given the same dose as someone with a healthy liver.

How Doctors Assess Liver Function

You can’t rely on a single lab value. AST and ALT? They don’t tell you much about drug metabolism. Bilirubin? Only part of the picture. The gold standard is the Child-Pugh-Turcotte score. It combines:- Bilirubin (above 3.0 mg/dL = Class C)

- Albumin (below 2.8 g/dL = Class C)

- INR (above 2.3 = Class C)

- Ascites

- Encephalopathy

Class A: Mild impairment. May need minor dose adjustments.

Class B: Moderate. Dose reductions of 25-50% for most drugs.

Class C: Severe. Often requires 50-75% reductions or complete avoidance.

Another tool gaining traction is the MELD score. For every 5-point increase above 10, drug clearance drops by about 15%. It’s becoming a go-to for predicting how a patient will handle medications.

What About Newer Drugs? Are They Safer?

Not necessarily. In 2023, the FDA approved 18 new drugs with specific dosing instructions for liver disease-a 25% jump from 2022. That’s because regulators now require hepatic impairment studies for nearly all new drugs. Since 2022, the EMA has made these studies mandatory. Some drugs are designed to be safer. Sugammadex, for example, is 96% cleared by the kidneys. No dose adjustment is needed-even in severe cirrhosis. But here’s the catch: while the drug itself is safe, recovery from neuromuscular blockade takes 40% longer in liver transplant patients. That’s still a risk.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: The Hidden Lifesaver

You can’t guess how a drug is behaving in a person with liver disease. Levels don’t correlate with lab values. A patient with mild fibrosis might have the same drug concentration as someone with full cirrhosis. That’s why therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is critical for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows: warfarin, vancomycin, phenytoin, lithium, and some antivirals. Measuring blood levels isn’t optional-it’s essential. A 2023 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics showed that using pharmacokinetic modeling to personalize doses reduced adverse events by 34.2%. That’s not a small gain. That’s life or death.What’s Changing Now? The Future of Dosing

The future isn’t about one-size-fits-all reductions. It’s about precision. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling now predicts drug exposure in liver disease with 85-90% accuracy. These models factor in:- Reduced liver blood flow

- Loss of liver cells

- Shunting

- Enzyme activity

The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance pushes for model-informed dosing. Experts predict that within five years, 70% of new drug labels will include PBPK-based dosing recommendations.

And it’s getting even more personal. Genetic differences matter. The CYP2C9*3 allele, found in 8.3% of Caucasians, slows warfarin metabolism. Combine that with cirrhosis? The risk of bleeding skyrockets. The next step? Testing for both liver function and genetic variants together.

Bottom Line: What You Need to Do

If you or someone you care for has liver disease:- Never assume a standard dose is safe.

- Ask if the drug is metabolized by the liver. Most are.

- Find out the Child-Pugh or MELD score. It’s more useful than AST/ALT.

- Push for therapeutic drug monitoring if the drug has a narrow window.

- Be extra cautious with opioids, benzodiazepines, and anticoagulants.

The system is catching up. But right now, the burden is on you and your prescriber to ask the right questions. Because in liver disease, the difference between healing and harm isn’t just about the drug-it’s about whether it was dosed right.

Can liver disease make drugs more toxic even if they’re not metabolized by the liver?

Yes. Even drugs cleared mostly by the kidneys can become riskier in liver disease. Why? The liver helps regulate protein binding and fluid balance. In cirrhosis, low albumin means more free (active) drug in the blood. Reduced kidney function from poor circulation also slows clearance. So, a drug like vancomycin or gentamicin-though not liver-metabolized-can still build up to dangerous levels.

Is it safe to use over-the-counter painkillers like acetaminophen with liver disease?

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is processed by the liver, and in advanced disease, even 2,000 mg per day can be risky. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends no more than 2,000 mg daily for patients with cirrhosis, and only if they don’t drink alcohol. Many doctors advise avoiding it entirely. NSAIDs like ibuprofen are even riskier-they can cause kidney failure in people with liver disease.

Why do some patients with liver disease handle drugs better than others?

Because liver disease isn’t one thing. Two people with the same Child-Pugh score can have very different enzyme activity, blood flow, and shunting. Genetics, alcohol use, fat buildup, and other illnesses all play a role. That’s why standard dose reductions are just a starting point. Personalized monitoring is the real solution.

Does fatty liver (MASLD) affect drug metabolism before cirrhosis?

Yes. Even early-stage metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) can reduce CYP3A4 activity by 15-25%. That’s enough to affect drugs like statins, some antidepressants, and calcium channel blockers. Many doctors still overlook this. If you have fatty liver, even without fibrosis, assume your drug metabolism is slower than normal.

What should I do if my doctor won’t adjust my dose for liver disease?

Ask for a consultation with a clinical pharmacist or hepatologist. Pharmacists are trained in drug metabolism and are often the best resource for dose adjustments. You can also request therapeutic drug monitoring. If your medication has a narrow therapeutic window, this isn’t optional-it’s a safety standard. Push for it. Your life depends on it.

Vitamin K Foods and Warfarin Interactions for INR Control

Vitamin K Foods and Warfarin Interactions for INR Control

The Connection Between Tendonitis and Lyme Disease: What You Need to Know

The Connection Between Tendonitis and Lyme Disease: What You Need to Know

Fake Generic Drugs: How Counterfeits Enter the Supply Chain

Fake Generic Drugs: How Counterfeits Enter the Supply Chain

Bupropion and Epilepsy: A Potential Treatment Option?

Bupropion and Epilepsy: A Potential Treatment Option?

Food Environment: How to Set Up Your Home Kitchen to Support Weight Loss Goals

Food Environment: How to Set Up Your Home Kitchen to Support Weight Loss Goals

Agnes Miller

February 16, 2026 AT 19:29just wanted to say i had a friend with cirrhosis who got prescribed oxycodone for back pain and ended up in the er with respiratory depression. they didn't adjust the dose. no one asked about liver function. it's scary how common this is.

Steph Carr

February 17, 2026 AT 18:56so let me get this straight - we’re telling people with failing livers to just ‘ask their doctor’ like that’s some magic wand? lol. the system is designed to ignore liver disease until someone’s already in a coma. we’ve got PBPK models that can predict toxicity with 90% accuracy… but insurance won’t cover TDM unless you’re dying. classic.

Geoff Forbes

February 18, 2026 AT 15:09the real issue isn't liver disease - it's that pharma companies design drugs for healthy people and then slap on a ‘use caution’ footnote. they don't test on cirrhotic patients because it's expensive. so we're left with doctors guessing. this isn't medical negligence - it's corporate greed dressed up as science.

Sam Pearlman

February 20, 2026 AT 08:38lol i'm a nurse in a hep unit and this post is 100% accurate. we had a guy on warfarin for afib, same dose for 3 years. got diagnosed with Child-Pugh B, didn't get adjusted. INR hit 12. he bled out in the hallway. no one checked his labs for months. it's not rare - it's routine.

Jonathan Ruth

February 21, 2026 AT 18:25acetaminophen at 2000mg is dangerous in cirrhosis? wow. next you'll tell me water can kill you if you drink too much. i mean really. we're reducing doses based on theoretical models while ignoring the fact that 80% of these patients are alcoholics who don't follow instructions anyway. this is overengineering a problem that could be solved with ‘don't drink and take meds’

Brenda K. Wolfgram Moore

February 23, 2026 AT 12:51thank you for writing this. i have MASLD and my doctor told me my statin dose was fine. i looked up CYP3A4 activity and realized he had no idea. i asked for a pharmacist consult and they cut my dose by 40%. no more muscle pain. this stuff matters. don't be afraid to push back.

guy greenfeld

February 25, 2026 AT 06:16what if the liver isn't the problem? what if the real issue is that the FDA, WHO, and AMA are all controlled by a shadowy alliance of Big Pharma and liver transplant conglomerates who profit from chronic illness? the ‘Child-Pugh score’? a marketing tool. the ‘MELD score’? a data trap. they want you dependent. they want you dosing wrong. they want you afraid.

Tony Shuman

February 27, 2026 AT 02:50americans think liver disease is just ‘alcoholics’ or ‘fat people’. newsflash - it's also from NAFLD, hepatitis C, autoimmune, and yes, even from taking too many ibuprofen for back pain over 10 years. and now we're telling them to ‘ask for a pharmacist’ like it's a luxury? we're in the richest country on earth and we still treat drug metabolism like a hobby. this is why other countries laugh at our healthcare.

Adam Short

February 27, 2026 AT 14:43you know what's wild? the same people who scream about ‘personalized medicine’ for cancer - the ones who demand genetic testing for every tumor - are the same ones who hand out standard doses of benzos to cirrhotic patients and call it ‘standard of care’. it's hypocrisy with a white coat.