People often use the words ulcers and gastritis interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing-even though they’re closely linked. Both cause stomach pain, bloating, and nausea. Both can be triggered by the same bacteria. But if you’re dealing with one, it doesn’t mean you have the other. Understanding the difference isn’t just about labels-it affects how you treat it, what medications you take, and whether you’re at risk for something more serious.

What is gastritis?

Gastritis is inflammation of the stomach lining. Think of it like a sunburn inside your stomach. The protective mucus layer gets damaged, and the tissue underneath becomes irritated. This can happen suddenly (acute gastritis) or over months or years (chronic gastritis).

The most common cause? Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a bacteria that lives in the stomach of nearly half the world’s population. It doesn’t cause problems for most people-but in some, it weakens the stomach’s defenses. Other triggers include long-term use of NSAIDs like ibuprofen or aspirin, heavy alcohol use, chronic stress, and autoimmune reactions where the body attacks its own stomach cells.

Symptoms vary. Some people feel nothing. Others get a burning pain in the upper abdomen, especially after eating. Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and feeling full too quickly are common. In severe cases, you might see blood in vomit or dark, tarry stools-signs the inflammation has caused bleeding.

What is an ulcer?

An ulcer is a break in the tissue. Specifically, a peptic ulcer is a sore that forms in the lining of the stomach or the first part of the small intestine (duodenum). Unlike gastritis, which is surface-level irritation, an ulcer is a deeper wound-like a crater in the stomach wall.

Most ulcers (about 80%) are caused by H. pylori. The rest are usually tied to NSAID use. These drugs block enzymes that protect the stomach lining. Without that protection, stomach acid eats away at the tissue, creating an open sore.

Ulcer pain is often described as a dull, gnawing ache. It typically comes and goes, sometimes worsening when the stomach is empty and improving after eating or taking antacids. But if the ulcer gets deep enough, it can bleed, perforate the stomach wall, or block food from passing through the digestive tract. These are medical emergencies.

How are they connected?

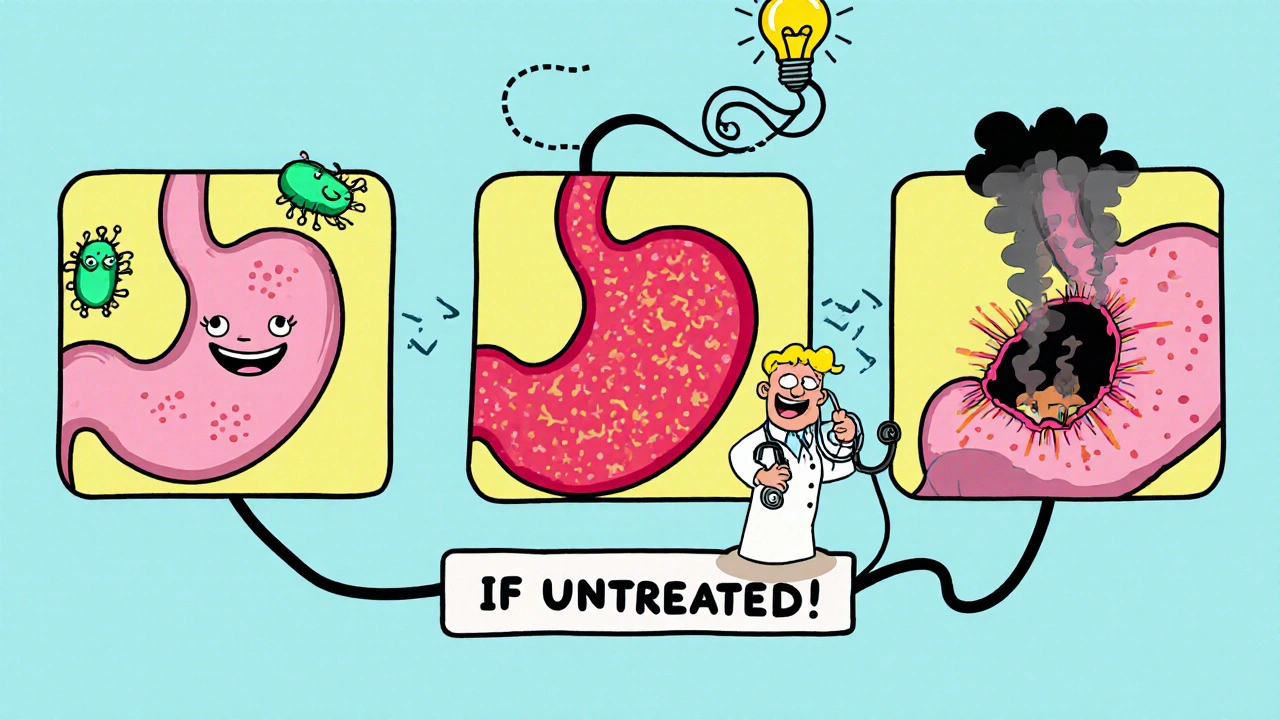

Here’s the key: gastritis often comes before an ulcer. When H. pylori or NSAIDs start damaging the stomach lining, the first sign is usually inflammation-gastritis. If the damage continues without treatment, the lining breaks down further, and an ulcer forms.

Studies show that up to 90% of people with peptic ulcers also have H. pylori infection, and nearly all of them show signs of gastritis first. It’s not a coincidence-it’s a progression. Think of it like a leaky roof: first, the paint peels (gastritis), then the wood starts rotting (ulcer).

Not everyone with gastritis gets an ulcer. Many people live with mild, chronic gastritis for years without developing sores. But if you have persistent symptoms, especially pain that doesn’t respond to antacids, you’re at higher risk.

How doctors tell them apart

Doctors don’t guess. They test.

For H. pylori, they might use a breath test, stool test, or blood test. But to see the actual damage, they need an endoscopy-a thin, flexible tube with a camera is passed down the throat to look directly at the stomach and duodenum.

During the procedure, they can spot the red, swollen patches of gastritis. They can also see the round or oval sores of an ulcer. If they find a sore, they’ll take a small tissue sample (biopsy) to rule out cancer and confirm the presence of H. pylori.

Ulcers show up as distinct breaks in the mucosal layer. Gastritis shows up as diffuse redness, swelling, or erosions-no deep holes. The difference is clear under the scope.

Treatment differences

Because they’re related, treatments overlap-but they’re not identical.

If H. pylori is the cause, both conditions are treated with a two-week course of antibiotics plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole. This combo kills the bacteria and reduces acid to let the tissue heal.

For gastritis caused by NSAIDs, stopping the drug and using a PPI is often enough. The lining usually heals on its own within weeks.

Ulcers require the same treatment-but healing takes longer. A small ulcer might take 4 to 8 weeks to close completely. If it’s large or bleeding, you might need hospitalization. Some ulcers need multiple rounds of treatment if the bacteria come back.

Antacids or H2 blockers like famotidine can ease symptoms, but they don’t cure the root cause. That’s why relying only on over-the-counter meds can be dangerous. You might feel better temporarily, but the damage keeps going.

What happens if you ignore it?

Left untreated, gastritis can lead to ulcers. Left untreated, ulcers can lead to complications:

- Bleeding: Ulcers can erode into blood vessels. You might vomit blood or pass black, sticky stools.

- Perforation: The ulcer burns all the way through the stomach wall. This causes sudden, severe pain and is life-threatening.

- Obstruction: Scar tissue from healing ulcers can block food from moving through the digestive system.

- Stomach cancer: Chronic H. pylori infection and long-term gastritis slightly increase the risk of gastric cancer over decades.

These aren’t rare. In the U.S., about 4 million people develop peptic ulcers each year. Around 60,000 are hospitalized for complications. Most cases are preventable with early diagnosis.

When to see a doctor

You don’t need to wait for a medical emergency. See a doctor if:

- Pain lasts more than a few days or comes back often

- Food or antacids don’t help

- You’re vomiting, especially if it contains blood or looks like coffee grounds

- Your stools are black, tarry, or bloody

- You’ve lost weight without trying

- You’re over 50 and have new stomach symptoms

These aren’t signs to brush off. Even if you think it’s just stress or spicy food, it could be H. pylori or an early ulcer.

Prevention tips

You can reduce your risk:

- Use NSAIDs only when necessary, and always take them with food or a stomach protector like misoprostol or a PPI.

- Limit alcohol. It irritates the stomach lining and makes H. pylori more harmful.

- Wash your hands regularly. H. pylori spreads through contaminated food and water.

- If you’ve had an ulcer before, get tested for H. pylori-even if you feel fine now.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking slows healing and increases the chance of ulcers coming back.

Most people recover fully with the right treatment. But ignoring symptoms is like ignoring a check engine light-you might keep driving, but the damage is getting worse.

Can gastritis turn into an ulcer?

Yes, gastritis can lead to an ulcer if the inflammation continues without treatment. The same factors that cause gastritis-like H. pylori infection or long-term NSAID use-can break down the stomach lining deeper over time, creating an open sore. Not everyone with gastritis gets an ulcer, but it’s a common progression.

Do ulcers and gastritis have the same symptoms?

They share symptoms like stomach pain, nausea, bloating, and feeling full quickly. But ulcer pain is often more localized, worse when the stomach is empty, and may improve after eating. Gastritis pain tends to be more generalized and constant. Ulcers can also cause bleeding, which is rare in mild gastritis.

Can you have an ulcer without gastritis?

It’s very rare. Almost all peptic ulcers occur in people who already have gastritis, usually from H. pylori or NSAID use. The inflammation comes first, then the ulcer. If you have an ulcer, you almost certainly have some level of gastritis, even if it’s mild or unnoticed.

Is H. pylori the only cause?

No. While H. pylori causes most cases, long-term use of NSAIDs like ibuprofen or aspirin is the second leading cause. Rarely, stress from major illness, burns, or surgery can cause ulcers. Autoimmune conditions can cause a type of gastritis that doesn’t involve H. pylori but can still lead to damage.

How long does it take to heal?

Gastritis usually improves in days to weeks with treatment. Ulcers take longer-typically 4 to 8 weeks for small ones, and up to 12 weeks for larger or bleeding ulcers. Treatment must continue even after symptoms go away to fully kill the bacteria and prevent recurrence.

Can stress cause ulcers?

Stress doesn’t directly cause ulcers, but it can worsen them. Severe physical stress-from trauma, burns, or critical illness-can lead to stress ulcers in the hospital setting. Emotional stress might make symptoms feel worse or slow healing, but it’s not the root cause. H. pylori and NSAIDs are the real culprits.

SSRIs and Opioids: Understanding Serotonin Syndrome Risk and How to Prevent It

SSRIs and Opioids: Understanding Serotonin Syndrome Risk and How to Prevent It

Pulmonary Hypertension: Recognizing Symptoms, Right Heart Strain, and Modern Therapy

Pulmonary Hypertension: Recognizing Symptoms, Right Heart Strain, and Modern Therapy

Tetracycline Photosensitivity: How to Prevent Sun Damage While Taking Antibiotics

Tetracycline Photosensitivity: How to Prevent Sun Damage While Taking Antibiotics

Wellbutrin Sr Prescription Online: Comprehensive Guide to Bupropion Treatment

Wellbutrin Sr Prescription Online: Comprehensive Guide to Bupropion Treatment

Don Angel

November 20, 2025 AT 06:43Wow, this is so well-explained. I always thought ulcers and gastritis were the same thing-turns out I was just lazy with my health info. Now I get why my doctor kept pushing for that breath test. I ignored it for months, and now I’m on antibiotics. Fingers crossed it sticks this time.

benedict nwokedi

November 20, 2025 AT 20:25Let me guess-Big Pharma wants you to believe H. pylori is the culprit so they can sell you antibiotics and PPIs forever. Meanwhile, the real cause? Glyphosate in your food, EMFs from your phone, and fluoride in the water. They don’t want you to know that your stomach lining is being chemically neutered by the system. Endoscopy? That’s just a distraction. The truth is buried under layers of corporate greed.

deepak kumar

November 22, 2025 AT 05:08As someone from India, I’ve seen this firsthand-people drink chai with too much sugar, eat spicy food daily, and pop ibuprofen like candy. Then they wonder why their stomach burns. H. pylori is everywhere here, but most don’t get tested until it’s too late. Please, if you have even mild discomfort for more than a week-get checked. It’s cheap, it’s easy, and it saves lives. Don’t wait like I did.

Dave Pritchard

November 23, 2025 AT 00:49Really appreciate how clearly this breaks it down. I used to think antacids were a fix, not just a band-aid. After my ulcer diagnosis, I stopped taking NSAIDs cold turkey-even my Advil for headaches. Took a while to adjust, but my stomach hasn’t felt this good in years. If you’re reading this and have chronic pain-don’t wait. Talk to your doctor. You’ve got this.

kim pu

November 24, 2025 AT 11:52Okay but… what if it’s not H. pylori? What if it’s the GMO corn syrup in your soda? Or the fact that your mom used bleach on your baby bottle as a kid? I had gastritis for 3 years. Took 12 different tests. Finally found out my gut was poisoned by… microwave popcorn bags. Seriously. The lining gets coated in PFAS. They don’t tell you that. They just hand you omeprazole and send you on your way. #GutConspiracy

malik recoba

November 25, 2025 AT 05:47i never knew gastritis could lead to an ulcer. i thought it was just ‘bad stomach’ and drank milk to fix it. turns out milk makes it worse? who knew. i’ve been having that gnawing pain for months. maybe i should go to the doc. i’m scared though. what if it’s bad?

Sarbjit Singh

November 26, 2025 AT 06:03Bro, I had this same issue last year. Took me 6 months to get tested. Finally did the breath test-positive for H. pylori. Antibiotics + PPI for 14 days. Boom. Gone. 🙌 Don't wait like I did. Your stomach ain't a vending machine. Treat it right!

Angela J

November 26, 2025 AT 19:13Did you know the government secretly uses H. pylori to control the population? They’ve been spraying it in public water systems since the 90s. That’s why everyone has stomach issues now. They want us weak. Depressed. Too tired to protest. And they make billions off the meds. I’m not paranoid-I’m informed. 😔

Sameer Tawde

November 28, 2025 AT 14:52Simple truth: if your stomach hurts for more than a week, see a doctor. No excuses. H. pylori is treatable. Ulcers heal. But ignoring it? That’s the real risk. You’re not invincible. Take care of your gut-it’s your first line of defense.

Erica Lundy

November 28, 2025 AT 20:11One is a surface disturbance of mucosal integrity; the other, a full-thickness breach of the epithelial barrier. The distinction is not merely clinical-it is ontological. To conflate the two is to reduce the phenomenology of bodily suffering to a diagnostic convenience. The body does not lie. The language we impose upon it, however, often does.