Lyme disease: what to watch for and what to do right away

A single tick bite can lead to Lyme disease, but catching it early usually makes treatment simple. This page gives clear, practical steps: how to spot early signs, what tests mean, when to start antibiotics, and how to prevent bites in the first place.

Recognize symptoms quickly

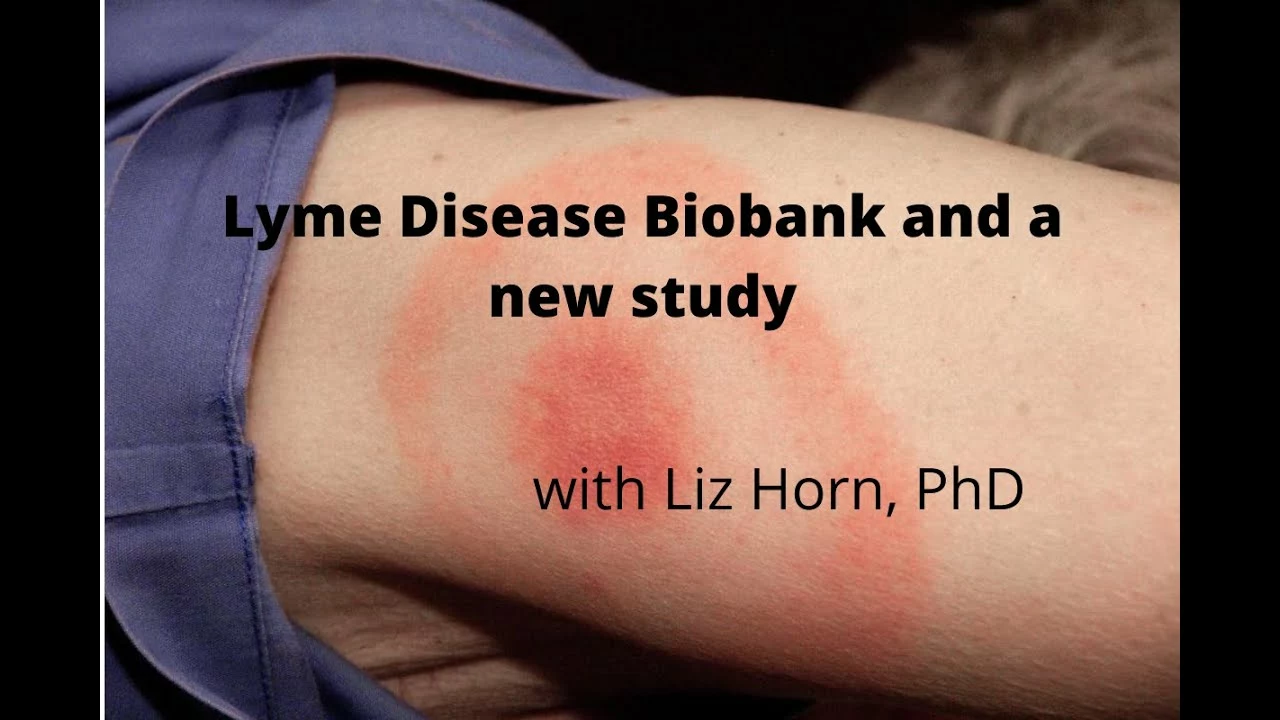

The most famous sign is a bull’s-eye rash (erythema migrans). It often appears 3–30 days after a bite and expands over days. Not everyone gets the classic bull’s-eye; some people have a flat red patch or no rash at all. Other early symptoms include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle or joint aches, and swollen lymph nodes.

If symptoms go untreated, Lyme can spread to joints, the heart, or the nervous system weeks to months later. That can cause severe joint pain, facial droop, palpitations, or nerve pain. If you develop any new unexplained symptoms after a tick bite, contact your clinician.

Diagnosis and treatment—simple rules

Doctors often diagnose Lyme disease by spotting a typical rash or by linking symptoms to a tick bite. Blood tests (ELISA followed by Western blot) are helpful but can be negative in the first few weeks. If you have a clear bull’s-eye rash, treatment usually starts without waiting for tests.

First-line treatment for most adults is doxycycline for 10–21 days. Alternatives include amoxicillin or cefuroxime for pregnant people and young children. A single-dose of doxycycline may be offered within 72 hours after a high-risk tick bite to prevent infection—ask your doctor if that’s right for you.

Some people report lingering fatigue or joint pain after treatment (called post-treatment Lyme symptoms). That’s a real problem for a minority, but extended antibiotics usually don’t help. If symptoms persist, see a specialist for symptom-based care and rehabilitation options.

Practical steps after a tick bite: remove the tick right away with fine-tipped tweezers—grip close to the skin and pull straight out. Don’t twist, don’t heat, and don’t use oil. Clean the bite with soap and water. Save the tick in a sealed bag if you want your doctor to ID it.

Prevention is the best plan. Wear long sleeves and pants in tick areas, tuck pants into socks, and treat clothes with permethrin. Use EPA-approved repellents with DEET or picaridin on skin. Shower and check your body within 2 hours of being outdoors; ticks are easier to spot and remove early. Keep yards tidy—short grass and a woodchip barrier cut down tick habitat.

When to see a doctor right away: any expanding rash, fever after a tick bite, facial weakness, sudden joint swelling, or new heart palpitations. If you’re unsure, call—early action can keep a short course of antibiotics from turning into months of problems.

Want links to reliable resources or current treatment guidelines? I can point you to CDC guidance and common clinical recommendations for easy reading.