Have you ever looked at a pill bottle and seen two different dates? One says expiration date, the other says beyond-use date? It’s confusing-and it shouldn’t be. These aren’t the same thing, and mixing them up could mean taking a pill that doesn’t work-or worse, one that’s unsafe.

What’s the Difference Between Expiration Dates and Beyond-Use Dates?

An expiration date comes from the manufacturer. It’s the last day they guarantee the medicine will work exactly as intended, based on lab tests done under strict conditions. Think of it like a warranty: if you store it right, it’s safe and strong until that date. These dates are required by law in the U.S. since 1979, and they’re backed by years of stability testing under controlled heat, light, and humidity levels. A beyond-use date (BUD) is different. It’s set by the pharmacy-not the drug company-when they change the medicine in any way. That could mean mixing powder into liquid, putting pills into a different container, or adding flavoring for a child. The original expiration date no longer applies. The pharmacist calculates a new date based on how stable the new version is, following USP guidelines. BUDs are almost always shorter than expiration dates because compounded medicines don’t have the same preservatives or packaging as factory-made drugs.When Do You See Each Date?

You’ll see an expiration date on any drug you buy off the shelf: antibiotics, blood pressure pills, pain relievers, even over-the-counter vitamins. It’s printed on the original bottle or box. If you never open it, it’s still good until that date. If you open it? The expiration date still stands-unless the pharmacy altered it. You’ll see a beyond-use date on:- Custom-made liquid medications (like a child’s version of a pill-only drug)

- Medications mixed with flavors or dyes to avoid allergies

- Pills repackaged into daily blister packs by a pharmacy

- IV bags or injections prepared in the pharmacy

How Long Do These Dates Last?

Expiration dates for commercial drugs usually range from 12 to 60 months after manufacturing. That’s because manufacturers test the drug under real-world storage conditions for years before approval. The FDA requires proof the medicine stays at least 90% potent until that date. BUDs are way shorter:- Non-sterile liquid formulations (like syrups): 14 days refrigerated

- Non-sterile solids (like capsules or tablets): up to 180 days at room temperature

- Repackaged pills (in blister packs): earlier of original expiration date or 1 year from repackaging

- Sterile injections: up to 45 days refrigerated, depending on risk level

Why Can’t You Just Use the Original Expiration Date?

Because the drug isn’t the same anymore. When a pharmacy alters it, they change its chemistry, stability, and risk profile. Say you have a pill that’s good until 2025. The pharmacy crushes it, mixes it with glycerin, and puts it in a dropper bottle. Now it’s a liquid. The sugar in the syrup can feed bacteria. The crushing process exposes the powder to air and moisture. The plastic dropper might leach chemicals. The original stability tests? They were done on the pill in its foil blister pack-not this new version. The manufacturer didn’t test this. So their expiration date doesn’t apply. Only the pharmacist’s BUD does.

What Happens If You Use a Drug Past Its Date?

Using a drug past its expiration date isn’t always dangerous-but it’s risky. The FDA tested over 100 drugs and found 90% still had at least 90% potency 15 years past their expiration date… if stored perfectly. But your medicine cabinet isn’t a lab. Heat, humidity, sunlight, and moisture degrade drugs faster. Antibiotics that lose potency can lead to treatment failure-and antibiotic resistance. Insulin, epinephrine, and nitroglycerin can become ineffective, which is life-threatening. Even painkillers might not work as well. Beyond-use dates are stricter because compounded drugs are more vulnerable. A liquid thyroid medication left on the counter for two weeks could grow mold. A repackaged antibiotic in a plastic container might break down into harmful byproducts.What Should You Do When You Get a Compounded Prescription?

When you pick up a compounded medication:- Check for both dates. The BUD should be clearly labeled on the container.

- Ask: Is this stored in the fridge? The pharmacy might have changed storage requirements.

- Don’t assume it’s good until the original bottle’s expiration date.

- Write the BUD on your calendar or set a phone reminder.

- If you don’t finish it by the BUD, bring it back to the pharmacy. Don’t toss it in the trash.

How Do Pharmacies Decide BUDs?

Pharmacists follow USP Chapter <795> guidelines. They look at:- The earliest expiration date of any ingredient used

- Whether the formula contains water (water = faster spoilage)

- Storage conditions (refrigerated? protected from light?)

- How complex the mixing process was

Why Do BUDs Vary So Much Between Pharmacies?

Because enforcement isn’t uniform. BUDs are regulated by state pharmacy boards, not the FDA. Some states follow USP guidelines strictly. Others are looser. That’s why two pharmacies might give you the same compounded drug with different BUDs. The FDA issued 27 warning letters to compounding pharmacies in 2022 for improper dating-up from 19 in 2021. That’s a red flag. Patients need to be vigilant.

Bupropion and Epilepsy: A Potential Treatment Option?

Bupropion and Epilepsy: A Potential Treatment Option?

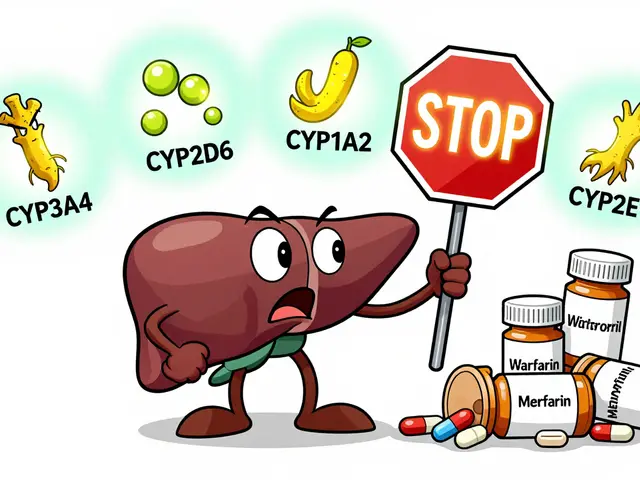

Goldenseal and Medications: What You Need to Know About Liver Enzyme Interactions

Goldenseal and Medications: What You Need to Know About Liver Enzyme Interactions

Terramycin vs Alternative Antibiotics: Tetracycline Comparison Guide

Terramycin vs Alternative Antibiotics: Tetracycline Comparison Guide

Wellbutrin Sr Prescription Online: Comprehensive Guide to Bupropion Treatment

Wellbutrin Sr Prescription Online: Comprehensive Guide to Bupropion Treatment

Bacterial vs. Viral Infections: What Sets Them Apart and How They're Treated

Bacterial vs. Viral Infections: What Sets Them Apart and How They're Treated

Windie Wilson

January 12, 2026 AT 22:00So let me get this straight - I pay $200 for a liquid thyroid med that expires in 14 days, but the original pill was good for 5 years? And if I don’t use it, I have to bring it back to the pharmacy like it’s a defective toaster? Welcome to American healthcare, folks.

Daniel Pate

January 13, 2026 AT 05:39The real issue isn’t the dates - it’s the lack of standardization. USP guidelines are suggestions, not laws. State boards enforce them inconsistently. That means your safety depends on which pharmacy you walk into. It’s not science - it’s roulette with your life.

Amanda Eichstaedt

January 15, 2026 AT 05:31I’m a mom of a kid with severe allergies, and I’ve had to use compounded meds for years. I didn’t know BUDs were so strict. I thought if the bottle said 2027, it was fine. Now I set reminders, refrigerate everything, and never trust the original label. This post saved me from a potential disaster.

Alex Fortwengler

January 15, 2026 AT 20:19They’re lying to you. The FDA knows most drugs last decades. The expiration dates are corporate lies to sell more pills. Compounding pharmacies? They’re just scared of lawsuits. If your insulin expires in 14 days, that’s because Big Pharma wants you to buy new ones. Wake up.

gary ysturiz

January 16, 2026 AT 04:05This is important info. If you’re taking anything compounded, treat the BUD like a deadline. Don’t guess. Don’t hope. Just follow it. Your health isn’t worth the risk. Thank you for sharing this clearly.

Jessica Bnouzalim

January 16, 2026 AT 06:44Wait - so if I repack my pills into a weekly pill organizer? I’m supposed to toss them after a year? Even if they’re still in the original foil? That’s insane! I’ve been doing this for years… I’m going to call my pharmacy right now.

laura manning

January 17, 2026 AT 11:23The author's assertion that "BUDs are non-negotiable" is statistically unsupported. The FDA’s Shelf-Life Extension Program demonstrated that 90% of drugs retained potency beyond expiration dates under controlled conditions. The variability in BUD enforcement reflects regulatory arbitrage, not pharmacological necessity.

Bryan Wolfe

January 18, 2026 AT 06:04Thank you for making this so clear. I used to think expiration dates were just "suggestions." Now I know - if it’s from the pharmacy and it’s mixed, changed, or repackaged, the BUD is your new Bible. Write it down. Set an alarm. Protect yourself. You’re worth it.

Sumit Sharma

January 19, 2026 AT 17:46The pharmacokinetic instability of non-sterile compounded formulations is well-documented in USP <795>. Water activity, microbial load, and degradation kinetics are non-linear post-reconstitution. The 14-day refrigerated BUD for liquid suspensions is conservative - many labs observe >10% potency loss by day 10. Compliance is not optional.

Jay Powers

January 20, 2026 AT 20:40Good post. I didn’t realize how much I didn’t know. I’ve been using my kid’s compounded meds past the date because they’re expensive. Now I’m going to ask my pharmacist about disposal programs. We all deserve safe meds, no matter the cost.

Lawrence Jung

January 21, 2026 AT 02:57Who really benefits from these BUD rules? Not patients. Not pharmacists. The real winners are the companies that make the original pills. They want you to keep buying. The science is manipulated. The dates are theater. You’re being played.

Lauren Warner

January 21, 2026 AT 12:42Let’s be honest - most people don’t read labels. They trust the pharmacy. And pharmacies? They’re overworked. They’re not always following USP guidelines. That’s why we have contamination outbreaks. This isn’t about dates - it’s about systemic neglect.

Lelia Battle

January 22, 2026 AT 15:30Thank you for this thoughtful breakdown. I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years, and I still see patients confused by these dates. The key is education - not fear. Clear labeling and open dialogue with patients can prevent so much harm.

laura manning

January 23, 2026 AT 16:41While the author correctly identifies the regulatory fragmentation, they omit the critical fact that USP <795> permits extended BUDs with stability data. Pharmacies that skip testing are negligent - not cautious. This is not a systemic flaw; it’s individual incompetence.

Darryl Perry

January 24, 2026 AT 07:21Stop wasting time with this. If you’re taking expired meds, you’re an idiot. If you’re ignoring BUDs, you’re a danger to yourself. This isn’t a debate. It’s basic survival. Get your facts straight or don’t take the pill.