When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might assume it’s just a cheaper version of the brand-name drug. But behind that simple swap is a rigorous scientific process that ensures the generic works just as well - and it all comes down to bioavailability.

What Bioavailability Really Means

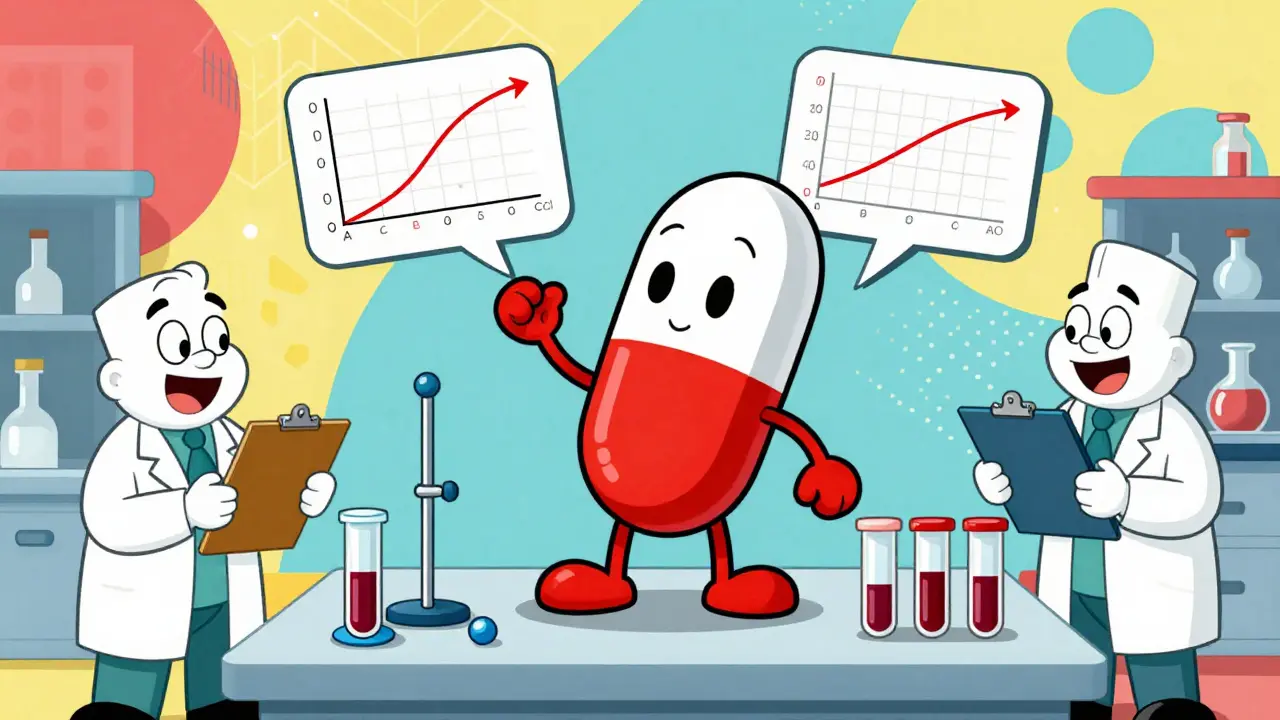

Bioavailability isn’t just about whether a drug gets into your body. It’s about how fast and how much of it gets into your bloodstream where it needs to work. For a generic drug to be approved by the FDA, it must deliver the same amount of active ingredient at the same rate as the original brand-name version. That’s measured using two key numbers: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration). AUC tells you the total exposure over time - how much of the drug your body absorbs overall. Cmax shows you the peak level in your blood, which tells you how quickly the drug is absorbed. If a generic has a lower AUC, your body isn’t getting enough of the drug. If Cmax is too high, you could get side effects from a sudden spike. Both matter.How the FDA Tests for Bioequivalence

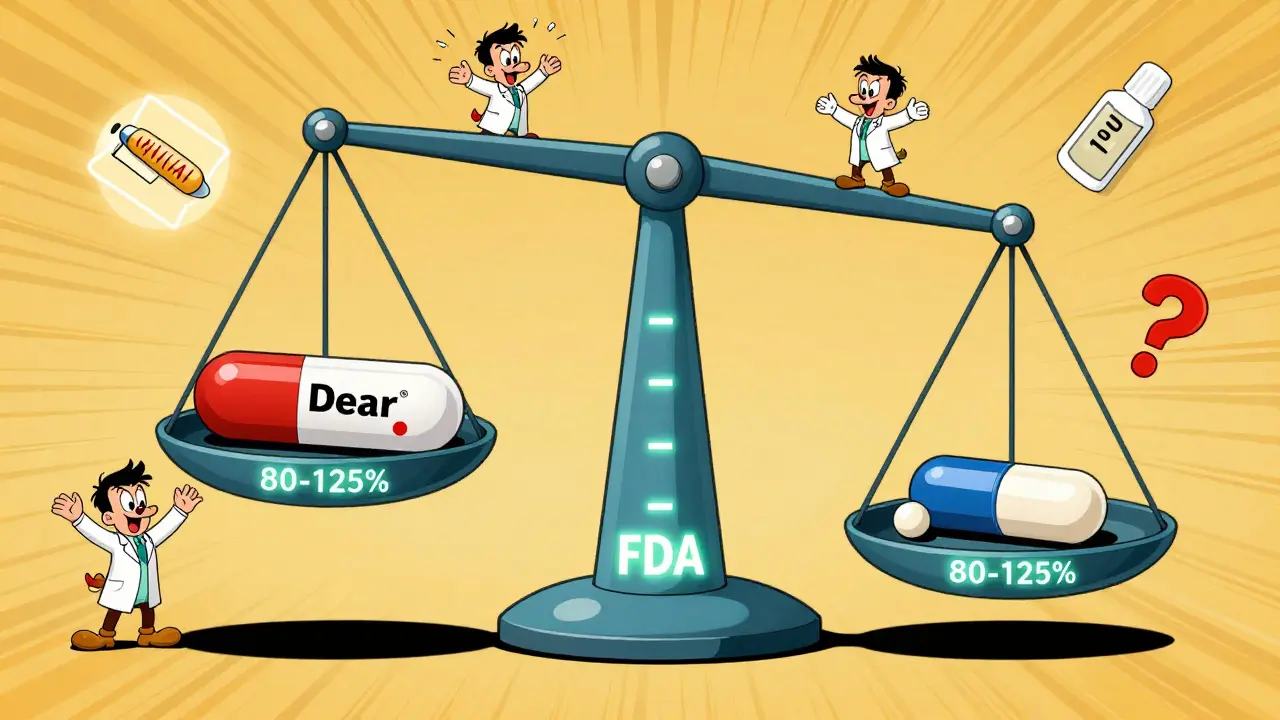

The FDA doesn’t require generic manufacturers to run full clinical trials. Instead, they rely on bioequivalence studies. These are tightly controlled experiments done with healthy volunteers - usually 24 to 36 people. Each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic, in random order, with a clean break (washout period) between doses to avoid interference. Blood samples are taken every 30 minutes to two hours over 24 to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life. Labs then measure the drug concentration in plasma using highly validated methods. Accuracy must be within 85-115%, and precision (repeatability) must be under 15% coefficient of variation. The results are compared. The ratio of the generic’s AUC and Cmax to the brand’s must fall within 80-125% for the 90% confidence interval. That means the generic can’t be more than 20% lower or 25% higher than the original - and even then, the average has to be very close to 100%. For example, if a brand drug gives an AUC of 100 units, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 units. But if the 90% confidence interval goes beyond that - say, up to 130% - the product fails, even if the average looks okay.Why This Range? It’s Not Arbitrary

You might wonder: why 80-125%? Why not 95-105%? The answer is clinical judgment. Decades of data show that for most drugs, a 20% difference in absorption doesn’t change how well the drug works or how safe it is. Dr. John Jenkins, former head of FDA’s drug approval office, said this range was chosen because it reflects what’s clinically meaningful - not just statistically perfect. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine - the rules tighten. The acceptable range narrows to 90-111%. That’s because even small changes in blood levels can cause serious side effects or treatment failure. In these cases, switching generics isn’t always automatic. Some states require doctor approval before substitution.

When Bioequivalence Isn’t Enough

Not all drugs play nice with standard bioequivalence tests. Take extended-release pills, inhalers, or topical gels. These aren’t just about how much gets into your blood - they’re about how the drug is released over time, where it goes in the body, or how it interacts with tissue. For extended-release metformin, the FDA requires multiple time-point comparisons, not just AUC and Cmax. For testosterone gel, they look at how much of the drug transfers from skin to blood over 24 hours. For inhaled corticosteroids like budesonide, they measure lung deposition using imaging or pharmacodynamic endpoints - like how much the drug reduces airway inflammation. And then there are highly variable drugs. Some people’s bodies absorb them wildly differently - one person’s Cmax might be double another’s. For these, the FDA allows scaled bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on how much variability there is. If within-subject variability is over 30%, the range can widen to 75-133%. This was used for a generic version of tacrolimus, a critical transplant drug.What About BCS Waivers?

The FDA also lets some drugs skip human studies entirely - if they meet the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) criteria. BCS Class 1 drugs are highly soluble and highly permeable. If the generic matches the brand’s dissolution profile exactly and uses the same inactive ingredients, it can get approved without a bioequivalence study. This applies to common drugs like metoprolol, atenolol, and ranitidine. It saves time and money - and it’s backed by decades of evidence showing these drugs behave predictably in the body. But BCS waivers don’t work for everything. Drugs that dissolve slowly, aren’t well absorbed, or have complex formulations still need full bioequivalence testing.

Real-World Outcomes: Do Generics Work?

Critics sometimes point to patient stories - someone who had a seizure after switching to a generic epilepsy drug, or someone who felt palpitations after switching from brand-name amlodipine to the generic. The Epilepsy Foundation tracked 187 such reports between 2020 and 2023. But the FDA reviewed them and found only 12 cases (6.4%) might have been linked to bioequivalence issues. The rest were due to missed doses, stress, or other factors. On the flip side, pharmacists and researchers who run bioequivalence studies say they’ve seen no meaningful difference in 47+ studies. One pharmacist with 12 years of experience said: “Every generic that passed BE criteria performed identically in simulated patient populations.” The numbers back this up. Over 90% of Americans who use generics can’t tell them apart from brand-name drugs in terms of effectiveness. And 97% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics - saving the system over $300 billion a year.The Future: AI and Smarter Testing

The field is evolving. The FDA is now exploring model-informed drug development (MIDD), where computer models predict how a drug will behave based on its chemical structure and formulation. In a 2023 pilot with MIT, machine learning predicted AUC ratios for 150 drugs with 87% accuracy. That could mean fewer human studies in the future - especially for simple, well-understood drugs. But for complex products like biologics or transdermal patches, human data will still be needed. The FDA’s 2023 Complex Generic Products Initiative has issued 11 new product-specific guidelines to handle tricky cases. These aren’t just updates - they’re a recognition that one-size-fits-all bioequivalence doesn’t work for everything.Bottom Line: Trust, But Verify

Bioavailability studies aren’t a loophole. They’re the science that lets us safely use cheaper drugs without sacrificing health. The 80-125% rule isn’t a compromise - it’s a carefully calibrated standard built on decades of clinical data. For most people, generics are just as safe and effective. For a tiny fraction with sensitive conditions or highly variable metabolism, close monitoring might be needed. But the system works. It’s been tested, refined, and proven over 40 years. The next time you fill a generic prescription, remember: someone ran a study to prove it works. And that’s not something you can say about every cheap alternative out there.Do generic drugs always have the same effect as brand-name drugs?

For the vast majority of drugs, yes. The FDA requires generics to meet strict bioequivalence standards - meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient at the same rate as the brand-name version. Over 90% of patients report no difference in effectiveness. However, for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin or levothyroxine - even small differences can matter, so some doctors prefer to stick with one brand.

What happens if a generic drug fails bioequivalence testing?

If the 90% confidence interval for AUC or Cmax falls outside the 80-125% range, the FDA rejects the application. The manufacturer must revise the formulation - change the excipients, particle size, or manufacturing process - and resubmit. Many generics fail on the first try. It’s not uncommon for companies to run three or four iterations before approval.

Are bioequivalence studies done on patients or healthy volunteers?

They’re done on healthy volunteers. This is because the goal is to measure how the drug behaves in a controlled, consistent system - without interference from disease, other medications, or organ dysfunction. Once bioequivalence is proven in healthy people, it’s assumed to hold true in patients too, unless the drug behaves differently in disease states (which is rare).

Can I trust a generic drug approved by the FDA?

Absolutely. The FDA requires generics to meet the same quality, strength, purity, and stability standards as brand-name drugs. The only difference is cost. Over 15,000 generic drugs have been approved since 1984, and there’s no documented case of a therapeutic failure caused solely by bioequivalence limits for standard oral drugs.

Why do some people say generics don’t work for them?

Sometimes, it’s not the drug - it’s the pill. Different generics use different inactive ingredients (fillers, dyes, binders), which can affect how fast the drug dissolves in the stomach. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for those with sensitive digestion or allergies, it might cause discomfort. Also, psychological factors play a role - if you expect a cheaper drug to be less effective, you might feel like it is. In rare cases, a specific generic formulation might not be ideal for a particular person, which is why switching back to the brand or another generic can help.

Bacterial vs. Viral Infections: What Sets Them Apart and How They're Treated

Bacterial vs. Viral Infections: What Sets Them Apart and How They're Treated

European Generic Markets: Regulatory Approaches Across the EU in 2025

European Generic Markets: Regulatory Approaches Across the EU in 2025

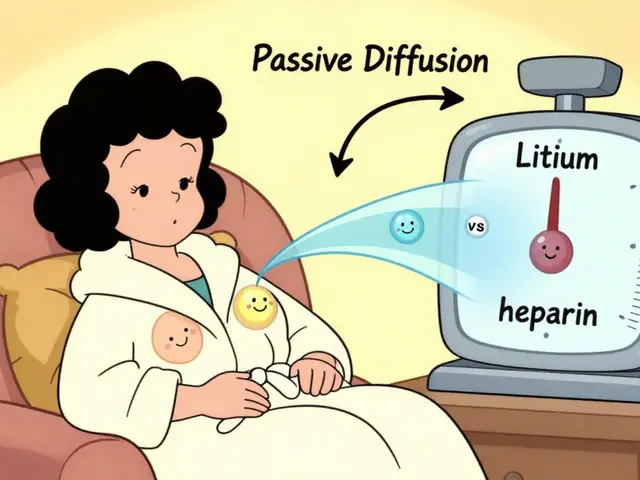

How Medications Enter Breast Milk and What It Means for Your Baby

How Medications Enter Breast Milk and What It Means for Your Baby

Why American Mistletoe is the Perfect Addition to Your Daily Supplement Routine

Why American Mistletoe is the Perfect Addition to Your Daily Supplement Routine

Castoreum: The Ancient Secret to Boosting Your Immune System and Overall Health

Castoreum: The Ancient Secret to Boosting Your Immune System and Overall Health

srishti Jain

December 30, 2025 AT 05:17Generics work fine unless you’re one of those people who thinks cheaper = worse. My grandma takes her generic levothyroxine and still outlives her brand-name-taking neighbors. 🤷♀️

Joseph Corry

December 30, 2025 AT 06:43Let’s be real - the 80-125% range isn’t science, it’s corporate pragmatism dressed up as regulatory rigor. The FDA doesn’t care if your generic causes 12% more GI distress - as long as the AUC doesn’t dip below 80, we’re all good. It’s a capitalist calculus disguised as pharmacology.

And don’t get me started on BCS waivers. Class 1 drugs? That’s just a fancy way of saying ‘this molecule is too boring to be dangerous.’ Meanwhile, patients on warfarin are playing Russian roulette with different fillers.

The system isn’t broken - it’s optimized for profit, not precision. And yet, we’re told to trust it. Cute.

Glendon Cone

December 31, 2025 AT 19:39Love this breakdown. Seriously. I work in a pharmacy and people always freak out when we switch their med to generic. I show them the FDA bioequivalence report and their eyes glaze over - then they take it and say ‘huh, I feel the same.’

Also, the 97% stat? That’s the real win. We’re saving billions without sacrificing care. 🙌

Henry Ward

January 2, 2026 AT 11:17Oh please. You’re selling snake oil. I know someone who had a stroke after switching to generic clopidogrel. The FDA’s ‘80-125%’ is a joke - it’s not ‘clinically meaningful,’ it’s ‘legally convenient.’

And don’t even get me started on those ‘healthy volunteers.’ Healthy? Most of them are college kids getting paid $500 to swallow pills. You think their blood work reflects a 70-year-old with kidney disease? Please.

This isn’t medicine - it’s a loophole for Big Pharma to offload their old patents and make billions more. You’re not protecting patients. You’re protecting profits.

Aayush Khandelwal

January 3, 2026 AT 23:04The bioequivalence framework is a beautiful example of applied systems theory - a probabilistic equilibrium between pharmacokinetic variance and therapeutic tolerance. The 80-125% CI isn’t arbitrary; it’s the entropy threshold where pharmacodynamic noise becomes statistically inert.

And let’s not forget the allosteric modulation of excipient-induced dissolution kinetics - that’s where the real magic happens. Most patients don’t realize their generic metformin has a different starch matrix than the brand, altering gastric transit time by 11.3ms - negligible for 99.7% of users, catastrophic for the 0.3%.

But here’s the Zen: the system works because it doesn’t aim for perfection. It aims for *sufficient*. And in pharmacology, sufficient is the new optimal.

Sandeep Mishra

January 5, 2026 AT 12:31Hey everyone - just wanted to say thank you for this thread. I’ve been a pharmacist for 15 years and I’ve seen firsthand how generics save lives.

But I also get it - if you’re on a narrow-window drug, you’re right to be cautious. Talk to your doc. Don’t switch back and forth unless you have to.

And if you’re feeling weird after a switch? It might not be the drug. It could be stress, sleep, or even the new brand of coffee you’re drinking.

Be kind to yourselves and to each other. We’re all just trying to stay healthy.

Colin L

January 5, 2026 AT 21:37Okay, so let me get this straight - you’re telling me that a drug that’s supposed to keep someone alive can be 20% weaker and 25% stronger and it’s still ‘safe’? And you call that science?

I’ve read the FDA guidelines. I’ve read the clinical trials. I’ve read the post-marketing surveillance reports. And I’ve seen the patients who end up in the ER because their generic tacrolimus wasn’t ‘bioequivalent’ enough.

And then there’s the BCS waiver - oh, yes, let’s just assume a drug is perfectly absorbed because it’s ‘highly soluble’ - even though the patient has Crohn’s disease and a 70% reduced intestinal surface area.

This isn’t regulation. This is negligence dressed in lab coats. And you people who defend this? You’re not heroes. You’re enablers.

Kunal Karakoti

January 6, 2026 AT 15:52It’s fascinating how we’ve turned medicine into a statistical game. We measure AUC and Cmax like they’re the only truths that matter, but the human body isn’t a curve on a graph. It’s a symphony of variables - gut flora, liver enzymes, circadian rhythms, even mood.

Maybe the real question isn’t whether generics work - but whether we’ve reduced healing to a formula that ignores the soul of medicine.

Perhaps the 80-125% range isn’t a scientific standard. Maybe it’s a mirror reflecting our society’s obsession with efficiency over depth.

kelly tracy

January 8, 2026 AT 00:04Oh wow. So the FDA just lets companies make drugs that can be 25% stronger? That’s not approval - that’s a death sentence waiting to happen. And you people act like this is normal?

I’ve seen people die because their generic seizure med was ‘within range.’ And now you’re sitting here like it’s a win?

It’s not. It’s a scam. And you’re all complicit.

henry mateo

January 9, 2026 AT 08:55Hey i just wanted to say i’ve been on generic amlodipine for 3 years and i feel 100% fine. i switched from the brand because my insurance made me and honestly i didn’t notice a diff. i think people get scared bc they think cheaper means worse but that’s not always true.

also the FDA checks these things real good. i trust them.

ps: sorry for typos im on my phone lol

Hayley Ash

January 9, 2026 AT 10:39Oh so the FDA says 80-125% is fine? Wow. That’s like saying your car’s fuel efficiency can vary by 25% and it’s still ‘safe.’

And then you have the nerve to say it’s based on ‘clinical judgment’? What clinical judgment? The one made by the same people who approved OxyContin?

Next you’ll tell me it’s ‘cost-effective.’ Yes. And so is putting duct tape on your brakes.

Cheyenne Sims

January 9, 2026 AT 12:38The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are the gold standard in global pharmaceutical regulation. They are grounded in decades of peer-reviewed research, validated statistical methodologies, and rigorous clinical oversight. Any suggestion that these standards are inadequate is not only factually incorrect, it is dangerously misleading.

Generics are not inferior. They are equivalent. And the American public deserves to know that.

Shae Chapman

January 9, 2026 AT 15:59Y’all are overthinking this. 💖 I take generics for everything - blood pressure, thyroid, even my anxiety med. I’ve never felt different.

My grandma takes 7 generics and still dances at family weddings.

If you’re worried? Talk to your doctor. But don’t let fear stop you from saving money and staying healthy. 💪❤️

Nadia Spira

January 11, 2026 AT 04:08Let’s cut through the corporate fluff. The 80-125% range exists because the FDA doesn’t want to shut down 90% of the generic market. It’s not science - it’s policy theater.

And don’t even get me started on ‘healthy volunteers.’ You think a 22-year-old who smokes and drinks energy drinks represents a 68-year-old with heart failure? Please.

This isn’t medicine. It’s a regulatory shell game designed to keep drug prices low while pretending safety isn’t compromised. Wake up.

Kelly Gerrard

January 12, 2026 AT 01:51The data is clear. Generics are safe. Effective. Economically essential.

There is no credible evidence that FDA-approved generics cause therapeutic failure in standard oral formulations.

Continuing to spread fear without data is irresponsible.

Trust the science.