When a nursing mother takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in her body. Some of it ends up in her breast milk-and that’s something every breastfeeding parent needs to understand. It’s not as scary as it sounds. Most medications transfer in tiny, harmless amounts. But knowing how and why this happens can help you make smarter choices without giving up breastfeeding.

How Drugs Get Into Breast Milk

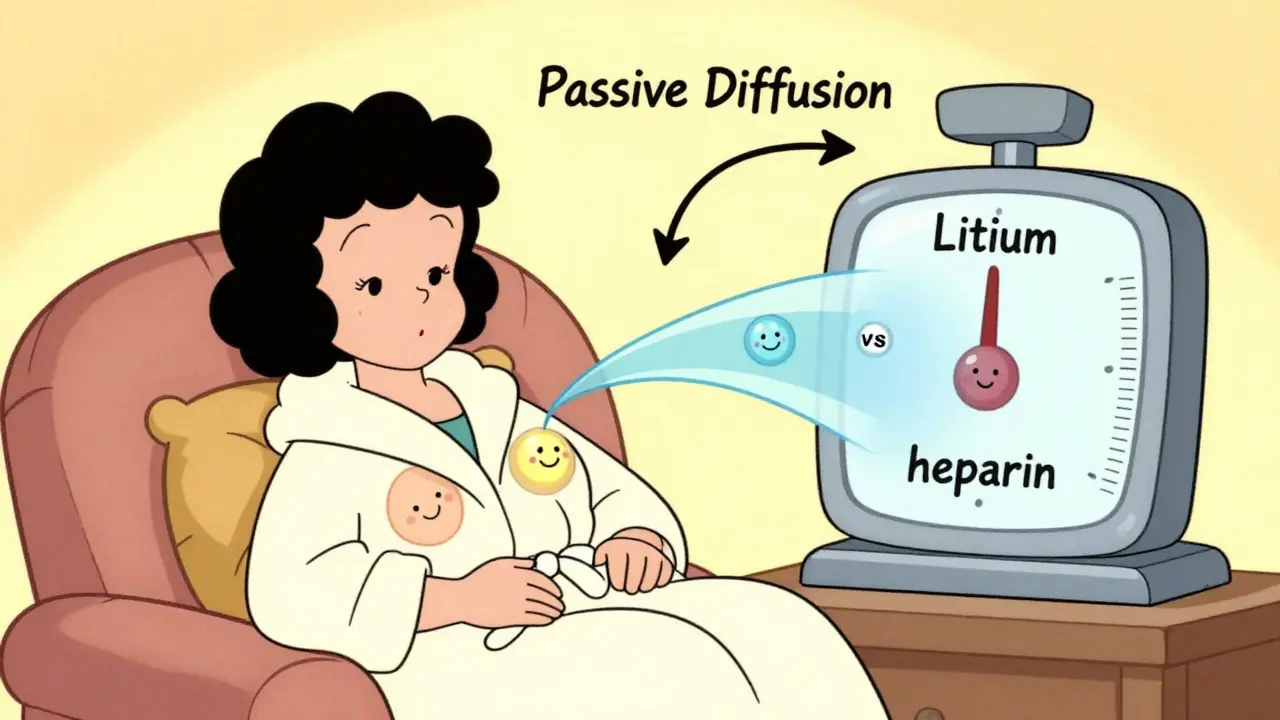

Medications don’t magically jump from your bloodstream into your milk. They move through your body the same way nutrients do. About 75% of drug transfer happens through passive diffusion. This means the drug molecules simply drift from areas of higher concentration (your blood) to lower concentration (your milk), crossing cell membranes along the way. Think of it like ink spreading in water-it goes where there’s space.

The other 25% moves via special transporters. Some drugs, like nitrofurantoin or acyclovir, latch onto protein carriers that normally move nutrients or waste. These carriers don’t care if they’re hauling a medicine instead of a vitamin-they just do their job. That’s why even drugs that seem too big or too water-soluble can still sneak into milk.

Three big factors decide how much gets through: molecular weight, lipid solubility, and protein binding.

- Molecular weight: Anything over 800 daltons barely makes it into milk. Heparin, for example, weighs 15,000 daltons-and less than 0.1% of the dose ends up in milk. But lithium, at just 74 daltons, passes easily.

- Lipid solubility: Fats love drugs. If a medication is oily (log P > 3), it slips through cell membranes like butter on toast. Diazepam, a common anti-anxiety drug, has a milk-to-blood ratio of 1.5-2.0. But gentamicin, a water-soluble antibiotic, barely registers-its ratio is 0.05.

- Protein binding: Most drugs in your blood are glued to proteins like albumin. Only the unbound portion can cross into milk. Warfarin, which is 99% bound, transfers less than 0.1%. Sertraline, even though it’s 98.5% bound, still gets through because there’s still a little unbound fraction.

There’s also something called ion trapping. If a drug is a weak base (pKa over 7.2), it gets pulled into milk because breast milk is slightly more acidic than blood. Amitriptyline, for example, can reach concentrations 2-5 times higher in milk than in your blood.

When Your Body Is Still Changing-The First 10 Days

Right after birth, your body isn’t fully set up for milk production. The tight junctions between the cells that make milk are still loose. During days 4 to 10 postpartum, gaps as wide as 10-20 nanometers exist. That’s big enough for large molecules-like antibodies and some drugs-to slip through easily.

This is why some medications that are normally safe can be riskier in the first week. After day 10, those junctions close up, and transfer drops by about 90%. So if you’re taking something during those early days, the amount your baby gets is higher than it will be later. That’s why timing matters.

How Much Actually Reaches Your Baby?

Most parents worry: “Is my baby getting a full dose?” The answer is almost always no. Infants typically receive less than 10% of the mother’s weight-adjusted dose. For most drugs, it’s closer to 1-3%.

Antibiotics like amoxicillin? About 1.5%. Gentamicin? Just 0.1%. Even antidepressants like sertraline result in infant exposure of only 1-2% of the maternal dose. Compare that to a newborn’s own metabolism-they’re tiny, but their livers and kidneys are working hard to clear what they get.

There are exceptions. Drugs with long half-lives in babies can build up. Diazepam, for instance, has a half-life of 30-100 hours in newborns (compared to 20-100 in adults). If you’re taking high doses-over 10 mg/day-your baby could accumulate enough to feel sleepy or fussy. That’s why doctors recommend checking infant serum levels if you’re on long-term benzodiazepines.

Another outlier: phenobarbital. In neonates, it can accumulate at a rate of 15% per week. That’s why monitoring is critical if you’re on seizure meds.

What’s Considered Safe? The Ratings System

Doctors and lactation consultants don’t guess when it comes to safety. They use systems like the Lactation Risk Categories developed by Dr. Thomas Hale and maintained by the InfantRisk Center.

Here’s how it breaks down:

- Level 1 (L1): No detectable transfer. Examples: insulin, heparin, most antacids.

- Level 2 (L2): Minimal transfer, no adverse effects reported. Examples: sertraline, amoxicillin, acetaminophen.

- Level 3 (L3): Possibly unsafe, but benefits may outweigh risks. Examples: fluoxetine, some beta-blockers.

- Level 4 (L4): Evidence of risk. Avoid unless no alternative. Examples: lithium (in high doses), cyclosporine.

- Level 5 (L5): Contraindicated. Examples: radioactive iodine-131, chemotherapy drugs like methotrexate.

Here’s the kicker: 87% of commonly prescribed medications fall into L1 or L2. That means most of what you’re on is likely fine.

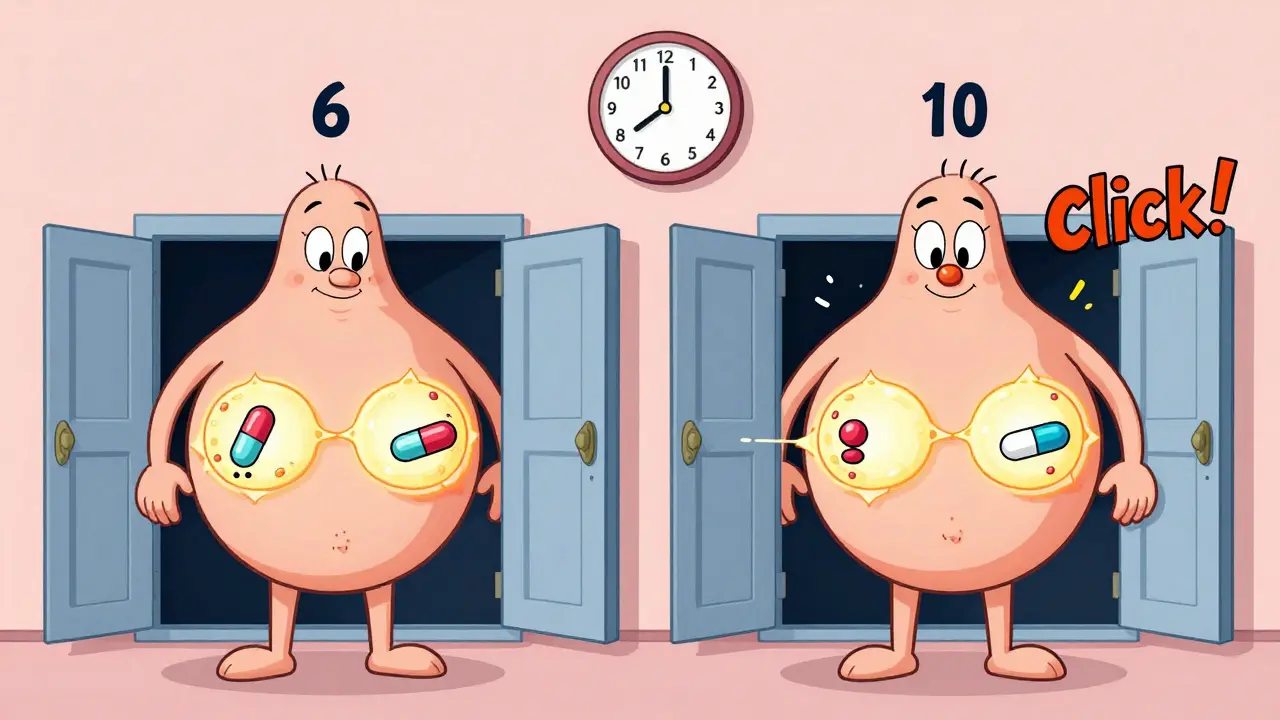

Timing Matters More Than You Think

When you take your pill can make a big difference. The best time? Right after you breastfeed.

Why? Because your blood concentration peaks 30-60 minutes after taking the drug. If you nurse right after, your baby gets the highest dose. But if you wait 3-4 hours, your blood levels have dropped by 30-50%. That simple trick cuts your baby’s exposure significantly.

This works especially well for drugs with short half-lives-like ibuprofen or amoxicillin. For long-acting ones, like extended-release antidepressants, you might need to space feedings differently. Always check with your provider.

What About Birth Control and Hormones?

Not all medications are equal. High-dose estrogen contraceptives-those with more than 50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol-are a known problem. They can slash milk supply by 40-60% within just 72 hours. That’s why progestin-only pills or non-hormonal options are recommended.

Bromocriptine? It’s designed to stop milk production. It’s used to treat high prolactin levels or after stillbirth-but if you’re trying to breastfeed, it’s a hard no.

What Should You Watch For?

Most babies show no symptoms. But if your baby becomes unusually sleepy, fussy, has trouble feeding, or develops a rash, it might be worth checking. These signs are rare, but they’ve been documented.

For SSRIs like sertraline, irritability shows up in about 8.7% of exposed infants. Poor feeding? Around 5.3%. These are mild and usually go away. But if your baby’s symptoms are new and coincided with starting a new medication, talk to your pediatrician. They can check serum levels if needed.

What About Nuclear Medicine and Imaging?

Some tests require special handling. A VQ scan using Tc-99m MAA? You’ll need to pump and dump for 12-24 hours. The radiation dose to the baby is low-about 0.15 mSv-but it’s still enough to warrant a pause.

But an FDG-PET scan? You can keep breastfeeding. Only 0.002% of the tracer ends up in milk. No interruption needed.

Always ask the radiology team for specific guidance. They’re trained in lactation safety.

The Big Picture: You’re Not Alone

Over half of breastfeeding mothers take at least one medication. Antibiotics, pain relievers, and antidepressants are the top three. Sertraline is the most common antidepressant used during lactation-3.2 prescriptions per 100 breastfeeding women each month.

Yet, 22.4% of mothers stop breastfeeding early because they’re worried about meds. That’s heartbreaking. Because here’s the truth: only 1-2% of medications absolutely require you to stop nursing. The rest? You can manage them safely.

Thanks to tools like the InfantRisk Center’s LactMed app (version 3.2, released Jan 2023), you can get real-time, science-backed answers. It uses 12 pharmacokinetic factors to assess risk-far more than a simple “yes or no.”

And now, the FDA requires all new drugs to include lactation data. That means the science is getting better, faster.

What’s Next?

The NIH-funded MOMS study (Maternal Outcomes and Medication Safety) is setting definitive safe exposure limits for 50 priority medications by 2025. That’s huge. It means we’ll soon have precise, evidence-based thresholds-not just general advice.

For now, the message is simple: Don’t stop breastfeeding because you’re on medication. Talk to your doctor. Use trusted resources. Time your doses. Monitor your baby. Most of the time, you and your baby will be just fine.

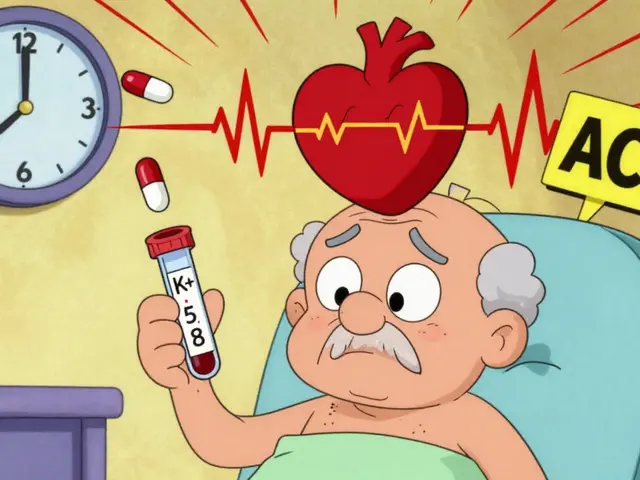

ACE Inhibitors with Spironolactone: Managing the Hyperkalemia Risk

ACE Inhibitors with Spironolactone: Managing the Hyperkalemia Risk

Rhabdomyosarcoma and Relationships: Supporting Your Partner Through Treatment

Rhabdomyosarcoma and Relationships: Supporting Your Partner Through Treatment

Exploring 5 Top Alternatives to Wellbutrin SR

Exploring 5 Top Alternatives to Wellbutrin SR

Tamoxifen and SSRIs: What You Need to Know About Drug Interactions and Breast Cancer Outcomes

Tamoxifen and SSRIs: What You Need to Know About Drug Interactions and Breast Cancer Outcomes

How to Compare Manufacturer Expiration Dates vs. Pharmacy Beyond-Use Dates for Medications

How to Compare Manufacturer Expiration Dates vs. Pharmacy Beyond-Use Dates for Medications

Patrick Jarillon

February 8, 2026 AT 01:11Did you know the FDA approves drugs based on lobbying money?

They don't care if your baby gets a tiny dose-they care if the pharma stock goes up.

That 'LactMed app'? Built by Big Pharma shills.

And 'ion trapping'? That's just a fancy word for 'your baby's getting drugged.'

My cousin took sertraline and her kid had seizures.

They said 'it's safe'-then buried the study.

They don't want you to know that 90% of meds are tested on rats, not humans.

And don't get me started on how breast milk is basically a drug delivery system designed by nature to be exploited.

They call it 'lactation safety'-I call it chemical coercion.

Wake up. The system is rigged.

Check the sources. Who funds the InfantRisk Center?

Ask yourself: Why are they pushing timing and dosing instead of saying 'just don't take it'?

They're not protecting you. They're protecting profits.

Sarah B

February 8, 2026 AT 01:52Tola Adedipe

February 8, 2026 AT 04:09Parents panic over meds because they think 'any drug = poison'.

Reality? Your baby's liver is a superhero.

They metabolize stuff way faster than adults.

That 1-3% exposure? It's less than what they get from environmental toxins in dust or air.

Stop letting fear drive decisions.

Use LactMed. Talk to a lactation consultant.

Don't quit breastfeeding because someone on Reddit said 'it's dangerous'.

Most of these meds are safer than stress.

Heather Burrows

February 8, 2026 AT 12:28It's very detailed.

Very scientific.

Very... unnecessary.

Why are we even discussing this?

Shouldn't we be asking why mothers have to take medication at all?

Why is our healthcare system so broken that breastfeeding moms need a pharmacology degree just to take ibuprofen?

It's not about the drugs.

It's about the society that forces this choice.

And the fact that we need an app to tell us what's safe?

That's the real tragedy.

Marcus Jackson

February 8, 2026 AT 19:50But here's the thing-people don't realize that 'barely' still means something.

And lithium? 74 daltons? That's like a sneeze in a hurricane.

And don't even get me started on diazepam.

That stuff sticks around like a bad ex.

My sister took 10mg/day and her kid was a zombie for three weeks.

Doctors say 'it's fine'-until the baby can't latch.

Then they say 'maybe it was the meds'.

So yeah, timing matters.

So does dose.

So does monitoring.

And no, LactMed doesn't cover everything.

It's a start.

Not a bible.

AMIT JINDAL

February 9, 2026 AT 03:29so like the body is just like a bouncer at a club right?

drugs tryna get in but only the cool ones with low weight and high lipid solubility get past

like diazepam? chillin in the VIP section while gentamicin is stuck outside like 'wtf man' 🤡

and ion trapping? that's just the milk being like 'yo you're a base? come in we got space'

and the first 10 days? those tight junctions are like a broken fence after a party

so yeah ur baby gets more then

after day 10? fence fixed 🛠️

also i think the whole '1-3%' thing is kinda chill but i still pump n dump after my anxiety meds just in case 😅

Lakisha Sarbah

February 10, 2026 AT 10:09Most moms don't need to be scared.

They need reassurance.

And information.

Not fearmongering.

Or apps.

Or charts.

Just someone to say: 'It's okay. You're doing great.'

That's all.

Not a 2000-word pharmacology lecture.

Just... love.

And a little trust.

Ariel Edmisten

February 10, 2026 AT 23:38Simple.

Works.

Don't overthink it.

Niel Amstrong Stein

February 11, 2026 AT 02:27Our bodies evolved to pass nutrients, not drugs.

But here we are-taking antidepressants like they're vitamins.

And somehow, the baby still thrives.

That's not science.

That's resilience.

That's love.

That's the human body saying: 'I don't care if you're chemically altered-I'm still gonna feed you.'

It's beautiful.

And kinda miraculous.

Also, emoji time: 🤱💕

Paula Sa

February 12, 2026 AT 09:46They're not just milk factories.

They're humans trying to survive depression, pain, infection, anxiety.

And yes, their babies get a trace of meds.

But they also get the love, the presence, the warmth.

That matters more than the 0.0001% of sertraline.

Let's not let pharmacology erase compassion.

Mary Carroll Allen

February 13, 2026 AT 20:29Why is there no simple list?

Why do I have to be a scientist to be a mom?

And why does every website have a disclaimer like 'this is not medical advice' like we're all just guessing?

It's 2025.

We have the data.

Why can't we just give moms a clear answer?

Also I think the 'pump and dump' thing is overblown.

My milk supply tanked when I started doing that.

So I just timed it.

And I'm still here.

And my baby is thriving.

And I'm not a hero.

I'm just trying to survive.

Joey Gianvincenzi

February 15, 2026 AT 18:37One must acknowledge the intricate interplay between pharmacokinetics and lactational physiology.

It is imperative that public health messaging not be diluted by emotive narratives.

While the emotional burden on lactating individuals is undeniable, the integrity of evidence-based practice must be preserved.

Furthermore, the regulatory oversight provided by the FDA and the InfantRisk Center constitutes a paradigmatic advancement in maternal-infant pharmacovigilance.

One must not conflate anecdotal experience with clinical reality.

Therefore, I urge all stakeholders to prioritize peer-reviewed data over social media speculation.

Respectfully submitted.

Ritu Singh

February 17, 2026 AT 07:36Most moms rely on grandmothers or local doctors who say 'avoid all meds'.

But what if you have severe depression?

What if you're in pain and can't even hold your baby?

We need simple, translated, culturally grounded guides.

Not just apps.

Not just American studies.

Real guides. In Hindi. In Tamil. In Bengali.

With pictures. With voices.

Because in rural villages, no one reads 2000-word posts.

They need one sentence: 'This medicine is safe. Keep feeding.'

Mark Harris

February 18, 2026 AT 20:30Don't let fear steal your joy.

Medication isn't failure.

It's self-care.

And breastfeeding? That's already a win.

Keep going. You're doing amazing.