Why a Renal Diet Matters for Kidney Health

If your kidneys aren’t working well, what you eat directly affects how sick you feel. The job of healthy kidneys is to filter waste, balance fluids, and keep electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorus in check. When kidney function drops-especially in stages 3 to 5 of chronic kidney disease (CKD)-those minerals start building up in your blood. Too much sodium makes you retain water, raising blood pressure and swelling your legs. High potassium can trigger irregular heartbeats, even cardiac arrest. Excess phosphorus pulls calcium from your bones, weakens them, and hardens your arteries. A renal diet isn’t about being perfect-it’s about reducing the strain on your kidneys so you stay healthier longer.

Sodium: The Hidden Culprit in Everyday Foods

The average person eats over 3,400 mg of sodium a day. For someone with CKD, the target is 2,000 to 2,300 mg-less than one teaspoon of salt. But you won’t find most of that sodium in the salt shaker. Around 75% comes from packaged, processed, and restaurant foods. A single serving of canned soup can have 800 to 1,200 mg. One slice of deli meat? Up to 600 mg. Even bread and cereal add up fast.

Reading labels is non-negotiable. Look for “no salt added,” “low sodium,” or “unsalted.” Avoid anything with sodium chloride, monosodium glutamate (MSG), baking soda, or sodium nitrate listed near the top of the ingredients. Use herbs like oregano, thyme, or garlic powder instead of salt. Mrs. Dash and similar herb blends work well. Cutting back by just 1,000 mg a day can lower systolic blood pressure by 5 to 6 mmHg, which reduces heart strain and slows kidney damage.

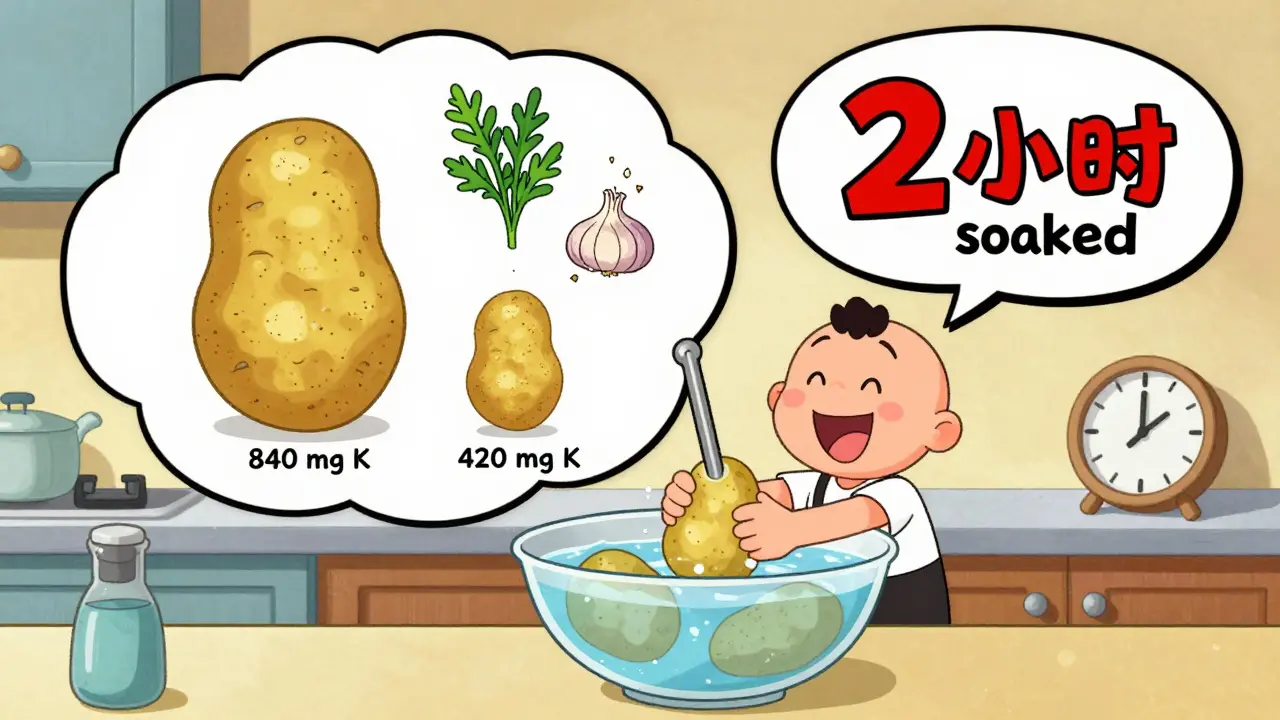

Potassium: Balancing the Good and the Dangerous

Potassium is essential for muscle and nerve function-but too much can be deadly. For CKD patients, the goal is usually 2,000 to 3,000 mg daily, but it depends on your blood levels. If your potassium hits 5.5 mEq/L or higher, you’re at risk for dangerous heart rhythms. The problem? Many “healthy” foods are packed with it. Bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, and avocados are all high. One medium banana has 422 mg. One cup of cooked spinach? 840 mg.

The trick is choosing lower-potassium options and using techniques like leaching. Leaching means peeling and slicing vegetables like potatoes or carrots, soaking them in warm water for 2 to 4 hours, then boiling them in a large pot of fresh water. This can cut potassium by half. Swap bananas for apples (150 mg each), oranges for berries (65 mg per half cup of blueberries), and spinach for cabbage (12 mg per half cup cooked). Also remember: potassium from animal foods like meat and dairy is absorbed more easily than from plants. So even if you eat less fruit, watch your milk, yogurt, and meat portions.

Phosphorus: The Silent Threat in Processed Foods

Phosphorus is tricky because not all of it is created equal. Natural phosphorus in foods like chicken, fish, beans, and dairy is only 40% to 70% absorbed. But inorganic phosphorus-added as preservatives or flavor enhancers in processed foods-is almost 90% to 100% absorbed. That’s why a can of cola has 450 mg of phosphorus, but a glass of milk has only 125 mg. One slice of processed cheese? 250 mg. Even some “healthy” protein bars and frozen meals are loaded with phosphate additives.

The recommended daily limit for non-dialysis CKD patients is 800 to 1,000 mg. To stay under that, avoid colas, processed meats, instant oatmeal, and anything with “phos” in the ingredients. Choose white bread over whole grain (60 mg vs. 150 mg per slice). Pick fresh chicken or fish over deli meats. Dairy is still okay in small amounts-half a cup of milk is fine, but skip the yogurt and cheese unless your dietitian says otherwise. New research shows that prebiotic fibers like inulin may help reduce phosphorus absorption by 15% to 20%, so including small amounts of asparagus, onions, or garlic could help.

Real Food Swaps That Actually Work

Changing your diet doesn’t mean eating bland, boring meals. It means swapping smart. Here are simple, proven swaps:

- Instead of white rice → try cauliflower rice (lower in potassium and phosphorus)

- Instead of whole wheat toast → try white bread or English muffins

- Instead of orange juice → try cranberry or apple juice (check labels for added potassium)

- Instead of salted nuts → try unsalted popcorn or rice cakes

- Instead of canned beans → try soaked and rinsed dried beans (leaching helps reduce potassium)

- Instead of frozen pizza → try homemade pizza with thin crust, low-phosphorus cheese, and veggies like zucchini or bell peppers

These swaps aren’t about deprivation-they’re about working with what your body can handle. Many patients report that after 3 to 6 months, their taste buds adjust. Spices, lemon juice, and vinegar become their new flavor boosters.

Fluids, Protein, and Other Key Considerations

Fluid intake matters too. If your kidneys aren’t making enough urine (less than 1 liter a day), you may need to limit fluids to 32 ounces daily. That includes water, coffee, tea, soup, ice cream, and even gelatin. Too much fluid can lead to shortness of breath, swelling, and high blood pressure.

Protein is another balancing act. Too little can lead to muscle loss and weakness, especially in older adults. Too much stresses the kidneys. The current recommendation is 0.55 to 0.8 grams of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight. That means a 70 kg (154 lb) person needs about 40 to 55 grams of protein daily. Good sources: egg whites, lean chicken, fish like cod or halibut, and tofu. Avoid processed meats like sausage or bacon-they’re high in sodium and phosphorus additives.

When to See a Renal Dietitian

Trying to manage sodium, potassium, and phosphorus on your own is hard. Blood levels change. Medications shift. Appetite fluctuates. That’s why working with a registered dietitian who specializes in kidney disease (an RDN) is one of the most effective things you can do. Medicare now covers 3 to 6 nutrition counseling sessions per year for stage 4 CKD patients because studies show it delays dialysis by 6 to 12 months and saves over $12,000 per patient annually.

A dietitian will review your lab results, track your food intake, and adjust your plan as your condition changes. They’ll also help you navigate the confusion around conflicting advice-like whether to cut phosphorus strictly or focus more on food quality. The latest guidelines from KDIGO (2023) stress individualized plans, not rigid rules.

Tools and Resources to Help You Stay on Track

Technology is making renal diets easier. The Kidney Kitchen app, downloaded over 250,000 times, lets you scan barcodes and see sodium, potassium, and phosphorus content instantly. Some hospitals now use AI-powered apps that sync with your electronic health records and adjust recommendations based on your latest blood work. In 2024, the Mayo Clinic began testing a system that sends real-time alerts if your daily intake trends toward dangerous levels.

There’s also new medical food like Keto-1, approved by the FDA in September 2023, designed to provide essential nutrients while keeping phosphorus and potassium low. And research is underway into genetic testing (the PRIORITY study, launched in January 2024) to predict how your body handles these minerals-potentially personalizing diets down to the individual.

What Doesn’t Work-and Why

Some people think cutting out all fruits and vegetables is the answer. That’s dangerous. Fiber, antioxidants, and vitamins from plants help reduce inflammation and protect your heart. The goal isn’t elimination-it’s smart selection and portion control.

Others believe they can just take a phosphate binder and eat whatever they want. Binders help, but they don’t replace diet. Studies show that even with binders, high phosphorus intake still increases heart disease risk.

And extreme protein restriction? It backfires. Research shows patients who eat less than 0.6g/kg/day are 34% more likely to become malnourished. The key is quality, not quantity.

Final Thoughts: It’s About Control, Not Perfection

A renal diet isn’t a punishment. It’s a tool to give you more time, more energy, and fewer hospital visits. You don’t have to be flawless. Miss a meal? Go back to plan tomorrow. Eat something high in potassium? Check your next blood test and adjust. Progress isn’t linear.

Focus on what you can control: reading labels, choosing fresh foods, leaching vegetables, using herbs, and staying in touch with your care team. The goal isn’t to live on rice and chicken forever-it’s to live well, with fewer complications, for as long as possible.

Celebrex: What You Need to Know About This Arthritis & Pain Relief Medication

Celebrex: What You Need to Know About This Arthritis & Pain Relief Medication

Pharmacist Substitution Authority: Understanding Scope of Practice in the U.S.

Pharmacist Substitution Authority: Understanding Scope of Practice in the U.S.

Floaters After Cataract Surgery: What’s Normal and What’s Not

Floaters After Cataract Surgery: What’s Normal and What’s Not

Esophageal Cancer Risk from Chronic GERD: Key Red Flags You Can't Ignore

Esophageal Cancer Risk from Chronic GERD: Key Red Flags You Can't Ignore

European Generic Markets: Regulatory Approaches Across the EU in 2025

European Generic Markets: Regulatory Approaches Across the EU in 2025

Manoj Kumar Billigunta

January 19, 2026 AT 17:33Don't let the fear of restrictions scare you. It's about adaptation, not deprivation.

clifford hoang

January 20, 2026 AT 08:47They’re hiding the truth. Phosphorus additives? Totally engineered by Big Pharma to keep you dependent on binders. Did you know the FDA approved Keto-1 the same week they passed the new kidney dialysis reimbursement rules? Coincidence? I think not.

And why are they pushing ‘low-phosphorus’ protein bars? Because they want you to buy their overpriced junk instead of real food. Wake up. Your kidneys aren’t failing-you’re being poisoned by the system. 🤔💊

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 22, 2026 AT 05:16Greg Robertson

January 24, 2026 AT 04:05Also, the Mayo Clinic real-time alert system sounds like sci-fi. Hope it rolls out soon.

Renee Stringer

January 25, 2026 AT 16:27Crystal August

January 27, 2026 AT 07:04Nadia Watson

January 28, 2026 AT 07:50Also, we make rice porridge with a little milk and sugar. It’s gentle on the kidneys. The cultural aspect matters. This guide is excellent, but I wish it included more global perspectives. Thank you for the work.

Courtney Carra

January 29, 2026 AT 14:18And yet, here we are. Choosing apples over bananas. White bread over whole grain. Like we’re playing Tetris with our own survival. Maybe the real question isn’t what to eat-but what kind of world forces us to make these choices?

Shane McGriff

January 29, 2026 AT 20:57Also, if you’re on the fence about seeing a renal dietitian-just do it. Medicare covers it. They’re not judging you. They’re helping you live longer. I wish I’d gone sooner.