When your kidneys start leaking protein, it’s not just a lab result-it’s your body screaming for help. For people with diabetes, this leak often starts quietly with something called albuminuria. It’s the earliest warning sign of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), a slow, silent killer that affects nearly 40% of adults with diabetes. But here’s the good news: catching it early and acting fast can stop it in its tracks. You don’t need a miracle. You need to know what to test for, when to test, and how to respond.

What Albuminuria Really Means

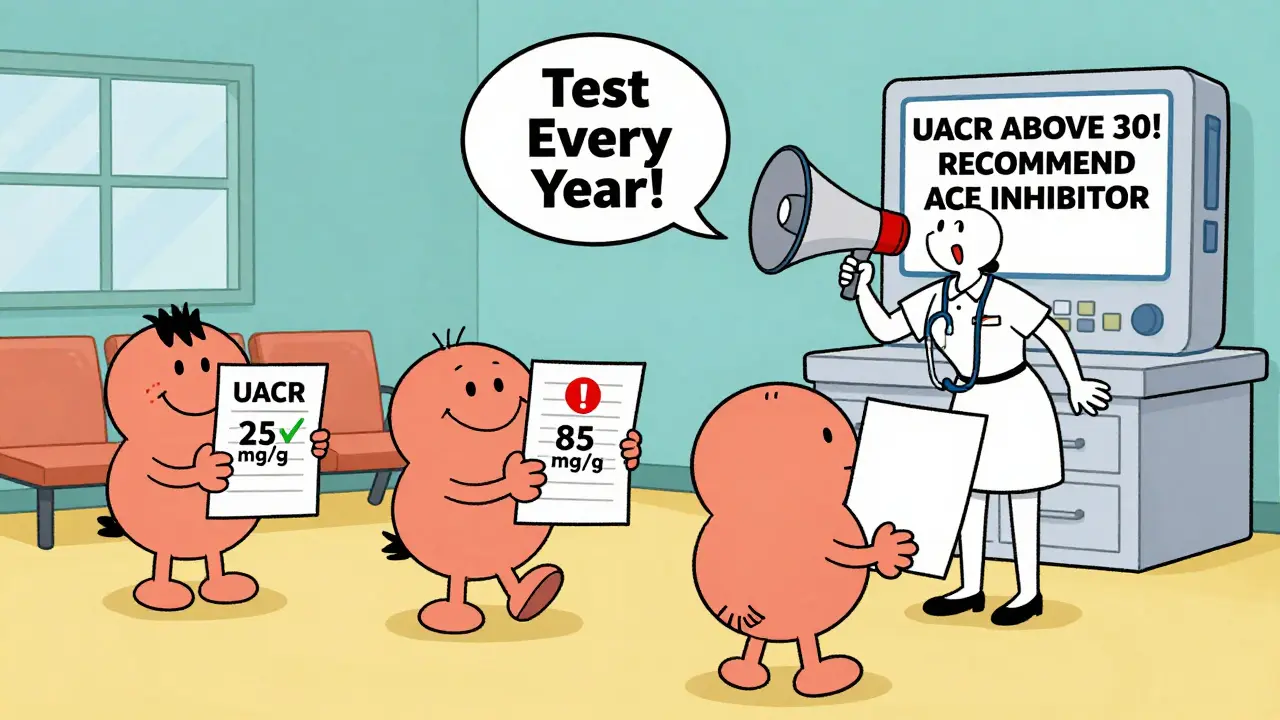

Albumin is a protein your kidneys normally keep inside your blood. When they start failing, it slips into your urine. That’s albuminuria. It’s not a disease itself-it’s a signal. Think of it like a smoke alarm. It doesn’t mean your house is burning down yet, but if you ignore it, it will be. The key measurement is the Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio, or UACR. It’s simple: you give a single urine sample, and the lab checks how much albumin is in it compared to creatinine (a waste product your body makes at a steady rate). This avoids the hassle of collecting urine over 24 hours. Here’s what the numbers mean:- Normal: Less than 30 mg/g

- Moderately increased: 30-300 mg/g (formerly called microalbuminuria)

- Severely increased: Over 300 mg/g (formerly macroalbuminuria)

Why You Can’t Trust a Single Test

One high UACR result doesn’t mean you have DKD. Not yet. Albumin levels can spike for all kinds of reasons-intense exercise, a fever, uncontrolled blood sugar over 300 mg/dL, a urinary infection, or even your period. That’s why guidelines say you need two out of three abnormal tests within three to six months to confirm diagnosis. If your first test shows 80 mg/g, don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either. Schedule a repeat test in 3 months. If it’s still above 30, you’re in the danger zone. And if it’s above 300? You’re already on the path to kidney failure if nothing changes.Albuminuria Is a Death Clock-But You Can Reset It

Let’s be blunt: albuminuria isn’t just a kidney problem. It’s a full-body emergency. A 2021 study of over 128,000 people with diabetes found that those with severely increased albuminuria (>300 mg/g) had a 73% higher risk of dying from any cause-and an 81% higher risk of dying from heart disease-compared to those with normal levels. Why? Because the same damage that leaks protein from your kidneys also damages your blood vessels. Your heart, brain, and legs are all at risk. Albuminuria is a mirror of your vascular health. Fix your kidneys, and you fix your heart.

Tight Control Isn’t Optional-It’s Survival

The best weapon against DKD isn’t a new drug. It’s control. Tight, consistent, long-term control. The landmark DCCT/EDIC study followed people with type 1 diabetes for over 30 years. Those who kept their HbA1c under 7% for years had a 39% lower chance of developing albuminuria and a 54% lower chance of progressing to proteinuria compared to those with average HbA1c near 9%. And here’s the kicker: the benefits lasted decades. Even after the strict control ended, their kidneys stayed healthier. That’s called “metabolic memory.” Your body remembers what you did to it. For type 2 diabetes, the UKPDS study showed that for every 1% drop in HbA1c, your risk of kidney disease drops by 21%. That’s not a small win. That’s life-changing. Current guidelines say most people with diabetes should aim for HbA1c under 7%. But if you’re young, healthy, and not prone to low blood sugar, aiming for 6.5% can offer even more protection. If you’re older or have heart problems, 7.5% might be safer. Personalization matters.Blood Pressure: The Second Pillar

High blood pressure doesn’t just hurt your heart-it crushes your kidneys. Every extra mmHg pushes more pressure through your fragile kidney filters, making them leak more protein. The KDIGO guidelines say if your UACR is above 300 mg/g, you should aim for blood pressure under 120/80 mmHg. That’s aggressive. And it works. The SPRINT trial proved that lowering systolic pressure to under 120 reduced the risk of macroalbuminuria by 39%. But it also increased the risk of sudden kidney injury in some people. That’s why the American Diabetes Association recommends a more practical target: under 140/90 mmHg for most people with DKD. The real goal isn’t hitting a number-it’s protecting your kidneys. And the best way to do that is with RAAS blockers: ACE inhibitors or ARBs. These drugs don’t just lower blood pressure. They directly protect the kidney’s filtering units. The IRMA-2 trial showed that losartan (100 mg/day) cut the progression from micro- to macroalbuminuria by 53%-even in people whose blood pressure was already normal. That’s why guidelines now say: start these drugs at the first sign of albuminuria, and titrate them to the highest tolerated dose.The New Game-Changers: SGLT2 Inhibitors and Finerenone

Medicine has moved beyond just controlling sugar and blood pressure. In 2023, the EMPA-KIDNEY trial showed that empagliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor) reduced the risk of kidney failure by 28% in people with DKD and UACR over 200 mg/g. It also lowered heart failure hospitalizations. And it works even if you’re not diabetic. Finerenone, a newer drug, blocks a hormone that causes kidney inflammation and scarring. In trials, it reduced albuminuria by 32% in just four months and slowed kidney decline by 23% over three years-even when patients were already on maximum ACE/ARB therapy. These aren’t add-ons. They’re now first-line treatments. The 2024 ADA/KDIGO guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for all patients with DKD and UACR over 30 mg/g, regardless of HbA1c. Finerenone is added if albuminuria remains high despite ACE/ARB and SGLT2i use.

Why Most People Don’t Get the Care They Need

Here’s the ugly truth: we know how to stop DKD. But we’re failing. NHANES data from 2017-2018 showed only 12.2% of adults with diabetes hit all three targets: HbA1c under 7%, blood pressure under 140/90, and LDL cholesterol under 100. That’s not a medical failure. It’s a system failure. In clinics, only 58-65% of patients get their UACR tested yearly-even though it’s a Class A recommendation (the highest level of evidence). Why? - 78% of clinics don’t have automated reminders in their electronic records - 23% of patients don’t return for repeat urine tests - Many doctors still think “microalbuminuria” is harmless The solution isn’t more drugs. It’s better systems. Clinics that use point-of-care urine testing cut follow-up loss by 37%. Pharmacist-led medication management gets 89% of patients on the right dose of ACE/ARB. EHR alerts that pop up when a patient’s UACR rises? They work.What You Can Do Right Now

If you have diabetes:- Ask for your UACR result at every annual checkup. Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- If your result is above 30 mg/g, get two more tests within six months. Confirm it.

- If confirmed, ask your doctor about starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB-even if your blood pressure is normal.

- Ask if you’re a candidate for an SGLT2 inhibitor like empagliflozin or dapagliflozin.

- Track your HbA1c every 3 months. Aim for under 7%.

- Keep your blood pressure under 140/90. If you’re on a blood pressure pill, make sure it’s an ACE or ARB.

- Don’t ignore infections, high blood sugar, or extreme exercise before testing. They can give false highs.

The Big Picture: Prevention Is Possible

The 2024 ADA/KDIGO consensus says that if we implemented existing guidelines fully, we could prevent 1.2 million new cases of diabetic kidney disease in the U.S. by 2030. That’s 37% fewer people needing dialysis. And $14.8 billion saved. This isn’t science fiction. It’s data. It’s proven. It’s doable. The problem isn’t that we don’t know how. It’s that we’re not doing it. Your kidneys don’t need a miracle. They need you to act early. To test regularly. To take your meds. To control your sugar. To speak up when something’s off. Because once albuminuria hits 300 mg/g, the race is on. And you don’t want to be running it alone.What is the difference between microalbuminuria and albuminuria?

There’s no real difference anymore. The term "microalbuminuria" (30-300 mg/g) was retired in 2012 by KDIGO guidelines because any albumin in the urine means kidney damage. The new terms are "moderately increased" (30-300 mg/g) and "severely increased" (>300 mg/g). The change was made to stop people from thinking small amounts are harmless.

Can albuminuria go away?

Yes, if caught early. Studies show that with tight blood sugar control, blood pressure management, and medications like ACE inhibitors or SGLT2 inhibitors, albuminuria can drop back into the normal range (<30 mg/g). This is called regression-and it’s linked to lower risk of kidney failure and heart disease. The earlier you act, the better your chances.

Do I need to do a 24-hour urine collection for albuminuria?

No. Spot urine tests (UACR) are now the standard. They’re easier, just as accurate, and more practical. A single morning sample is enough. Timed collections (like overnight) are only used in research or if the spot test is unclear.

Why do I need to test my UACR every year if I have diabetes?

Because DKD develops slowly and silently. By the time symptoms appear-swelling, fatigue, foamy urine-the damage is often advanced. Annual UACR screening catches it early, when it’s still reversible. The American Diabetes Association gives this recommendation the highest level of evidence (Class A) because it saves kidneys and lives.

Can I stop my diabetes meds if my albuminuria improves?

No. Even if your UACR drops to normal, you still need to keep taking your medications. The drugs that protect your kidneys-like ACE inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, and finerenone-work by reducing inflammation and pressure inside your kidneys. Stopping them risks a rebound in albuminuria and faster kidney decline. Treatment isn’t a cure; it’s ongoing protection.

Does diet play a role in managing albuminuria?

Yes, but not in the way most people think. A low-sodium diet helps control blood pressure. A balanced diet that manages blood sugar and weight reduces overall stress on your kidneys. But there’s no "kidney diet" that magically removes albuminuria. Protein restriction is no longer recommended unless you’re in late-stage kidney disease. Focus on whole foods, limit processed carbs, and avoid excess salt.

What if I can’t afford the new medications like finerenone or SGLT2 inhibitors?

Talk to your doctor. Many drug manufacturers offer patient assistance programs. Generic ACE inhibitors and ARBs are inexpensive and still highly effective. SGLT2 inhibitors like dapagliflozin are now available as generics in many countries. If cost is a barrier, your doctor can prioritize based on your risk level. The most important thing is to start with what’s accessible-control your blood sugar and blood pressure first.

Can exercise cause false albuminuria?

Yes. Intense exercise within 24 hours of a urine test can temporarily raise albumin levels. So can fever, heart failure, or uncontrolled high blood sugar. If your test comes back high, ask your doctor if any of these factors might be involved. Don’t assume it’s kidney damage until you’ve ruled them out with repeat testing after 3-6 months.

Rheumatoid Arthritis Medications: How DMARDs and Biologics Interact in Treatment

Rheumatoid Arthritis Medications: How DMARDs and Biologics Interact in Treatment

Discover the Life-Changing Benefits of Lithium: The Essential Dietary Supplement

Discover the Life-Changing Benefits of Lithium: The Essential Dietary Supplement

Abhigra vs Other Sildenafil Brands: Full Comparison

Abhigra vs Other Sildenafil Brands: Full Comparison

Diabetic Kidney Disease: How Early Albuminuria Signals Risk and Why Tight Control Saves Kidneys

Diabetic Kidney Disease: How Early Albuminuria Signals Risk and Why Tight Control Saves Kidneys

Pharmacist Concerns About NTI Generics: What Every Provider Needs to Know

Pharmacist Concerns About NTI Generics: What Every Provider Needs to Know

Danielle Stewart

December 19, 2025 AT 03:39Just got my UACR results back-42 mg/g. I was scared, but this post gave me a roadmap. Started on losartan last week and dropped my HbA1c to 6.8% with daily walks and cutting out soda. It’s not perfect, but I’m not ignoring it anymore. Small steps, big wins.

mary lizardo

December 20, 2025 AT 01:40One must question the epistemological foundations of this so-called 'guideline.' The term 'microalbuminuria' was retired not due to scientific consensus, but due to bureaucratic inertia and pharmaceutical lobbying. The KDIGO guidelines are not gospel-they are a reflection of institutional capture. To treat 30 mg/g as pathology is to medicalize normal human variation.

jessica .

December 20, 2025 AT 21:38They want you to take these drugs because Big Pharma owns the FDA. Albuminuria? That’s just your body detoxing from the glyphosate in your corn syrup and the fluoridated water they pump into your town. They don’t want you to heal-they want you hooked on ACE inhibitors forever. Wake up.

Ryan van Leent

December 21, 2025 AT 22:51Why are we even talking about this? If you’re diabetic and not controlling your sugar then you’re just lazy. No one’s forcing you to eat donuts at 2am. Stop making it a medical crisis and take responsibility. I’ve seen people die from this and it’s always because they didn’t listen

Isabel Rábago

December 23, 2025 AT 05:27My dad had DKD. He ignored his UACR for years because his doctor said 'it's just a little protein.' By the time they acted, his kidneys were at 18% function. I don't care what the guidelines say-I’ve seen the aftermath. If your urine test is above 30, treat it like a fire alarm. Not a suggestion.

Anna Sedervay

December 23, 2025 AT 17:47While the empirical data presented is statistically significant, one cannot overlook the epistemic limitations of observational cohort studies-particularly those derived from NHANES, which are subject to confounding by socioeconomic stratification. The purported 'metabolic memory' effect may be an artifact of residual confounding, and the use of SGLT2 inhibitors as first-line therapy represents a paradigmatic overreach, especially in the absence of long-term mortality data in non-diabetic populations.

Matt Davies

December 25, 2025 AT 04:32Man, this post is like a lighthouse in a hurricane. I’m a type 2 guy with a UACR of 89, and I thought I was fine until I read this. Started on dapagliflozin last month, lost 12 pounds, my BP’s down, and I actually feel lighter-like my body’s finally getting a break. If you’re reading this and scared? Good. Now go ask for that test. Your future self will high-five you.

Ashley Bliss

December 25, 2025 AT 12:46They say 'act early'-but early for whom? The system doesn’t care if you’re uninsured, working two jobs, or can’t afford the copay for an ACE inhibitor. This isn’t about willpower. It’s about a society that turns medical emergencies into personal failures. My sister died waiting for a kidney transplant because her insurance denied the test. So don’t preach 'control' to people who are drowning in bills and bus schedules.

holly Sinclair

December 26, 2025 AT 06:08It’s fascinating how albuminuria functions as a biomarker of systemic vascular decay-not merely renal dysfunction. The kidney, in this context, is less an organ and more a canary in the coal mine for endothelial integrity. The fact that SGLT2 inhibitors exert renoprotective effects independent of glycemic control suggests a pleiotropic mechanism involving tubuloglomerular feedback modulation and reduced intraglomerular pressure. But this raises a deeper philosophical question: are we treating disease, or are we merely managing the symptoms of a metabolic civilization that has outpaced biological adaptation? The real tragedy isn’t the protein in the urine-it’s that we’ve normalized metabolic dysfunction as the price of modernity.

Monte Pareek

December 26, 2025 AT 13:21Look I’ve been in diabetes care for 22 years and I’ve seen this play out a thousand times. The people who live are the ones who test every year. The ones who die? They didn’t know their UACR number. They thought 'micro' meant 'minor.' It doesn’t. It means 'now.' Start the ACE inhibitor. Get the SGLT2i. Hit that HbA1c. Don’t wait for symptoms. You won’t get any until it’s too late. I’ve got patients in their 80s walking fine because they acted at 50. You can too. Just do the damn work.

Allison Pannabekcer

December 26, 2025 AT 22:04Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I see so many patients scared to ask for tests because they feel judged. This post doesn’t judge. It empowers. I’m printing it out and handing it to every diabetic patient I see. And if you’re reading this and you’re worried-reach out. You’re not alone. We’ve got your back.

Sarah McQuillan

December 27, 2025 AT 05:29Actually, the real problem is that people with diabetes are getting too much attention. Why not focus on curing cancer or Alzheimer’s instead of micromanaging urine tests? I mean, if you eat sugar and get sick, isn’t that just evolution at work? Maybe the body is supposed to fail this way. Maybe we’re just supposed to accept it and move on. Stop medicalizing everything.