Celiac disease in children isn’t just about stomachaches or bloating. It’s a silent thief of growth, energy, and long-term health-unless caught early and managed right. Many kids with celiac disease don’t look sick. They might just be shorter than their peers, tired all the time, or picky eaters. But behind those symptoms is an autoimmune reaction that’s slowly destroying the lining of their small intestine. Without gluten-free eating, their bodies can’t absorb the nutrients needed to grow, think, or thrive. The good news? When diagnosed and treated properly, most children catch up fully-and live healthy, normal lives.

Why Growth Problems Are a Red Flag

In kids, celiac disease often shows up as poor growth. Not every child will have diarrhea or vomiting. Some just stop gaining weight or growing taller at the expected rate. This isn’t random. The immune system attacks the villi-the tiny finger-like projections in the small intestine that absorb nutrients. When those villi flatten, up to 90% of the surface area for nutrient absorption is lost. That means less iron, less vitamin D, less protein-all the building blocks of growth. Studies show that 10 to 40% of children brought in for evaluation because they’re short for their age turn out to have undiagnosed celiac disease. One key clue? Delayed bone age. If a 7-year-old’s wrist X-ray shows the bones of a 5-year-old, that’s a major red flag. It means the body has slowed down its growth clock to compensate for poor nutrition. The good part? When gluten is removed, that clock often restarts. Children with delayed bone age at diagnosis have a 95% chance of reaching their full genetic height potential. Those without it? Only about 65% do.How Celiac Disease Is Tested Today

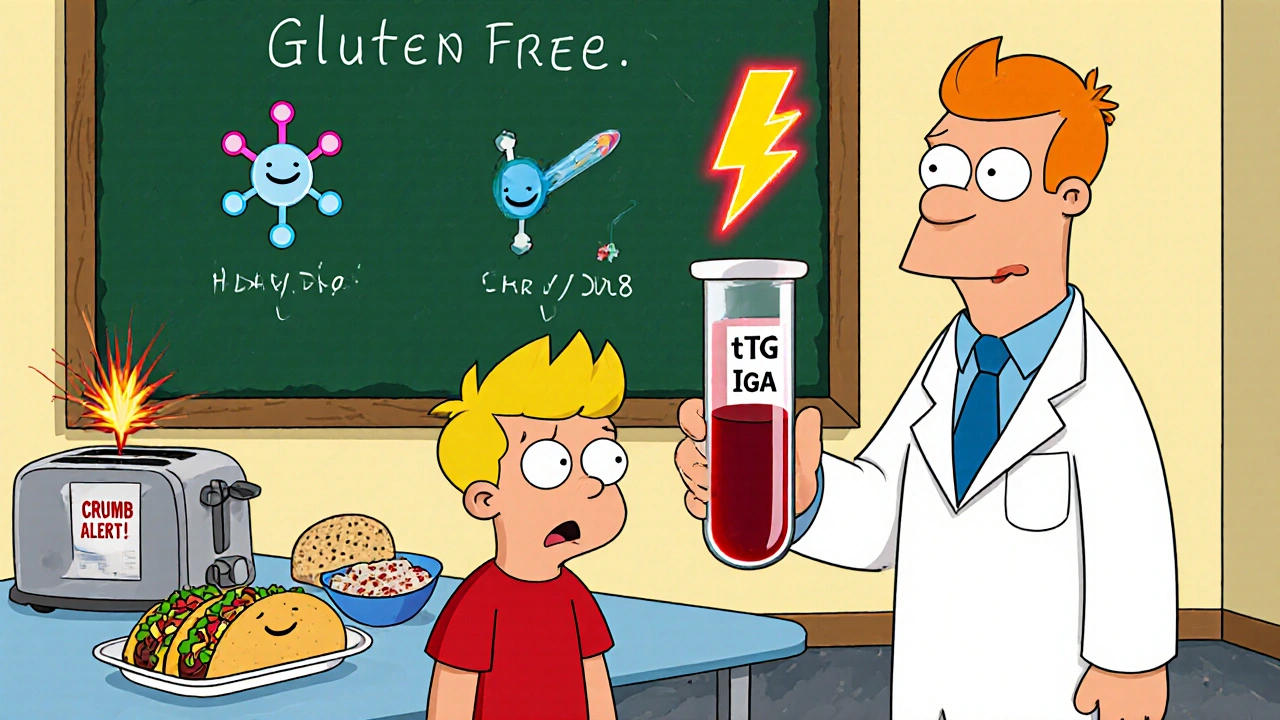

Testing has gotten smarter. The first step is a simple blood test: tTG-IgA (tissue transglutaminase antibody). It’s accurate in 98% of cases when the child is still eating gluten. But there’s a catch: if the child is IgA deficient (which happens in 2-3% of celiac patients), the test can miss the disease. That’s why doctors always check total IgA levels at the same time. If tTG-IgA is more than 10 times above normal, and the child has symptoms, and carries the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 genes (which 95% of celiac patients do), a biopsy might not even be needed. That’s a big shift from just five years ago. The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology updated its guidelines in 2020 to allow diagnosis without endoscopy in these clear-cut cases. It means fewer needles, less sedation, and faster answers for families. For borderline cases, or if the blood test is normal but suspicion is high, a biopsy is still the gold standard. During an endoscopy, tiny samples are taken from the small intestine. In active celiac disease, you’ll see Marsh 3 lesions-complete or near-total flattening of the villi. Bone age X-rays and blood tests for iron, vitamin D, and folate are also routine. About half of newly diagnosed kids are iron deficient. Two-thirds have low vitamin D. These aren’t side effects-they’re direct results of damaged intestines.What Happens When Gluten Is Removed

The moment gluten is cut out, the healing begins. But it’s not instant. Weight usually improves within 6 months. Kids start gaining pounds, their appetite returns, and they stop feeling sluggish. Height? That takes longer. Most children gain 2 to 4 centimeters per year above their expected rate in the first year on a gluten-free diet. Catch-up growth can take 18 to 24 months. Some kids, especially those diagnosed after age 5, never fully close the gap-but they still get much closer than they would have without treatment. One study tracked 24 children diagnosed at an average age of 8.3 years. Before diet, their height was nearly 2 standard deviations below average. After three years on a gluten-free diet, they were still below average-but only by 0.95 standard deviations. That’s a huge improvement. And 85% of all children with celiac disease reach their target height by adulthood if they stick to the diet. Iron and vitamin D levels also bounce back, but slowly. It can take up to two years for bone mineral density to normalize. That’s why supplements are often needed-not as a cure, but as a bridge while the gut heals.

Diet Adherence: The Hardest Part

The diet is simple: no wheat, barley, rye. But in practice? It’s one of the most challenging diets in pediatrics. Gluten hides everywhere. Soy sauce. Malt vinegar. Some medications. Even playdough. Cross-contamination is a nightmare. A single crumb from a shared toaster can trigger symptoms in a sensitive child. Studies show 40 to 50% of households have cross-contamination issues. And 58% of children with celiac disease get accidentally exposed at school. That’s why 504 plans are critical. Schools need to know: no sharing food, separate utensils, trained staff, and gluten-free options in the cafeteria. Adherence drops sharply in adolescence. Teens want to fit in. They skip meals, eat pizza at parties, or think “just a little won’t hurt.” But even small amounts of gluten keep the immune system active. That means ongoing damage-even if they don’t feel sick. About 20 to 30% of kids show persistent antibodies on blood tests, despite thinking they’re eating clean. That’s why quarterly tTG-IgA checks are non-negotiable. The cost is another barrier. Gluten-free products cost 156 to 242% more than regular ones. For many families, that’s not just inconvenient-it’s impossible. Community support groups help. Families who join local celiac chapters see adherence rates jump by 25 to 30%.What to Watch For Beyond Growth

Growth is the headline, but celiac disease affects more than height. About 15 to 20% of kids at diagnosis have delayed puberty. Iron deficiency anemia is common-up to 15% of cases. Vitamin D deficiency can lead to rickets or weak bones. Folate and B12 levels often drop, affecting brain development and energy. Some children don’t improve even with perfect diet adherence. That’s rare-but it happens. If a child isn’t gaining height or weight after 12 to 18 months on a strict gluten-free diet, other issues need to be ruled out: thyroid problems, growth hormone deficiency, or even another autoimmune condition like type 1 diabetes (which is common alongside celiac). The long-term risks of ignoring the diet are real. Adults who had undiagnosed celiac as children have a 2 to 3 times higher risk of intestinal lymphoma. That’s why lifelong adherence isn’t optional. It’s life-saving.

Real Stories, Real Results

One mother in Perth told us her 6-year-old son was in the 5th percentile for height and constantly tired. After diagnosis, he started gaining 30 grams a day. Within six months, he was back on the growth curve. By 18 months, he’d caught up to his twin brother. He’s now 12, plays soccer, and eats gluten-free pasta without complaint. Another family struggled for two years. Their 14-year-old daughter was always “just tired.” She missed school, avoided friends, and refused to eat anything outside the house. After diagnosis, she started feeling better in two weeks. But the social isolation? That took longer. With school support and a local celiac teen group, she’s now a peer advocate. She says, “I used to feel broken. Now I feel strong.”What Parents Need to Know

If your child is short, slow to gain weight, or unusually tired, ask about celiac disease. It’s not rare. One in 133 children in the U.S. has it. In Australia, the rate is similar. Early diagnosis means full recovery. Delayed diagnosis means years of missed growth and unnecessary suffering. Work with a pediatric dietitian. Don’t guess. Learn how to read labels. Check for “malt,” “modified food starch,” and “hydrolyzed wheat protein.” Keep a food and symptom diary. Test antibodies every 6 to 12 months. And never, ever let your child go back to gluten-even if they say they feel fine. Their body is still being damaged. The future is bright. Clinical trials are exploring pills that block gluten’s effects or train the immune system not to react. But right now, the only proven treatment is the diet. And it works-if you stick with it.Can a child outgrow celiac disease?

No. Celiac disease is a lifelong autoimmune condition. It does not go away, even if symptoms improve. The only treatment is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet. Even small amounts of gluten can cause damage to the intestines, even if the child doesn’t feel sick.

How long does it take for a child to grow after starting a gluten-free diet?

Weight usually improves within 6 months. Height catch-up takes longer-typically 18 to 24 months. Some children, especially those diagnosed early, catch up fully. Others may still be slightly shorter than peers but reach their full genetic potential. Growth velocity increases by 2-4 cm per year above expected rates in the first year on the diet.

Is a biopsy always needed to diagnose celiac disease in children?

Not always. If a child has tTG-IgA levels 10 times higher than normal, carries the HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 genes, and has clear symptoms, a biopsy may be skipped under current ESPGHAN 2020 guidelines. This avoids unnecessary procedures in about half of diagnosed cases. But if test results are borderline or symptoms are unclear, a biopsy is still required for confirmation.

What nutrients are most commonly low in children with celiac disease?

Iron, vitamin D, folate, and vitamin B12 are the most common deficiencies at diagnosis. About 30-50% of children have low iron levels, and 40-60% have low vitamin D. These deficiencies cause fatigue, poor bone development, and delayed growth. Supplementation is often needed while the gut heals, which can take 1-2 years.

How do you know if a child is truly following a gluten-free diet?

The best way is through regular tTG-IgA blood tests. Antibody levels should drop to normal within 6-12 months of starting the diet. If they stay high, it suggests ongoing gluten exposure-even if the family thinks they’re being careful. Weight gain, improved energy, and normalized growth are also signs of adherence, but blood tests are the only objective measure.

Can gluten-free products be trusted?

Look for certified gluten-free labels (under 20 ppm). Not all “gluten-free” products are safe. Cross-contamination in factories is common. Stick to brands with certification, especially for grains like oats, which are often processed with wheat. Homemade meals using whole foods (fruits, vegetables, meat, rice, quinoa) are safest.

Why do some children still have symptoms after going gluten-free?

If symptoms continue after 6-12 months on a strict gluten-free diet, there may be accidental gluten exposure, another condition like lactose intolerance (common after gut damage), or a different illness such as thyroid disease or growth hormone deficiency. A pediatric gastroenterologist should re-evaluate the child in these cases.

Is celiac disease genetic?

Yes. Children with a first-degree relative (parent or sibling) with celiac disease have a 5-10% chance of developing it by age 10. Genetic testing for HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 can help assess risk, but having the genes doesn’t mean the child will get celiac-it just means they’re susceptible. Environmental triggers like infections or dietary changes often play a role in when it develops.

Proven Strategies to Prevent Osteoporosis - A Complete Guide

Proven Strategies to Prevent Osteoporosis - A Complete Guide

Hyaluronic Acid Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis: What Really Works

Hyaluronic Acid Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis: What Really Works

Chronic Gastroenteritis: Causes, Symptoms, and Management

Chronic Gastroenteritis: Causes, Symptoms, and Management

Vantin (Cefpodoxime) vs Alternative Antibiotics: Which Works Best?

Vantin (Cefpodoxime) vs Alternative Antibiotics: Which Works Best?

How to Audit Your Medication Bag Before Leaving the Pharmacy: A Simple 7-Step Safety Check

How to Audit Your Medication Bag Before Leaving the Pharmacy: A Simple 7-Step Safety Check

Jacob Hepworth-wain

November 29, 2025 AT 07:06My niece was diagnosed at 5. She went from barely hitting the 10th percentile to the 50th in 18 months. No magic pills, just no gluten. It’s wild how something so simple can change everything.

Leah Doyle

November 30, 2025 AT 00:00I’m a mom of a 9-year-old with celiac and this hit me right in the feels. The part about teens skipping meals? So real. My daughter used to cry before school lunches. Now she brings her own and even teaches her friends how to read labels. She’s not broken-she’s brilliant.

Craig Hartel

December 1, 2025 AT 06:06Just moved from the US to Japan last year and the gluten-free scene here is wild. No certified labels, no easy options. But we found this tiny bakery in Osaka that makes rice-based bread that’s actually good. My kid finally stopped asking why everyone else gets pizza. Small wins, you know?

Chris Kahanic

December 2, 2025 AT 19:17The data on bone age and catch-up growth is compelling. I work in pediatric endocrinology and see this regularly. The real challenge isn’t diagnosis-it’s sustaining adherence over years. Especially when the kid feels fine. The body doesn’t feel damage until it’s too late.

Aarti Ray

December 3, 2025 AT 12:59in india its so hard to find gf food and no one understands why we cant eat roti or naan. my son was diagnosed last year and we had to start cooking everything from scratch. its expensive but worth it. his energy is back and he smiles again

Alexander Rolsen

December 4, 2025 AT 05:12Why do we even allow this? Gluten is poison. It’s not a fad. It’s not a trend. It’s a silent killer disguised as bread. And the food industry knows it. They hide it in sauces, meds, even lip balm. Someone needs to sue these corporations.

tom charlton

December 4, 2025 AT 17:42As a pediatrician, I’ve seen too many children misdiagnosed as picky eaters or having ‘slow growth’ when celiac was the root cause. The 2020 ESPGHAN guidelines were a game-changer. Avoiding unnecessary endoscopies in clear cases reduces trauma for families and accelerates care. We must educate primary care providers-this isn’t rare, it’s under-recognized.

Alexis Mendoza

December 5, 2025 AT 07:08It’s funny how something so basic-eating-can be so complicated. But the body knows what it needs. When you stop feeding it the wrong thing, it starts healing itself. No magic, no pills. Just truth. And patience. And a lot of rice.

Michael Segbawu

December 7, 2025 AT 03:12AMERICA IS THE ONLY COUNTRY THAT GETS THIS RIGHT. EVERYONE ELSE IS JUST PLAYING AROUND. MY SON GOT DIAGNOSED AT 6 AND NOW HE’S ON THE HONOR ROLL. NO OTHER COUNTRY HAS THE RESOURCES OR THE WILL TO FIX THIS. IF YOU’RE NOT DOING A GLUTEN FREE DIET YOU’RE PUTTING YOUR KID IN DANGER